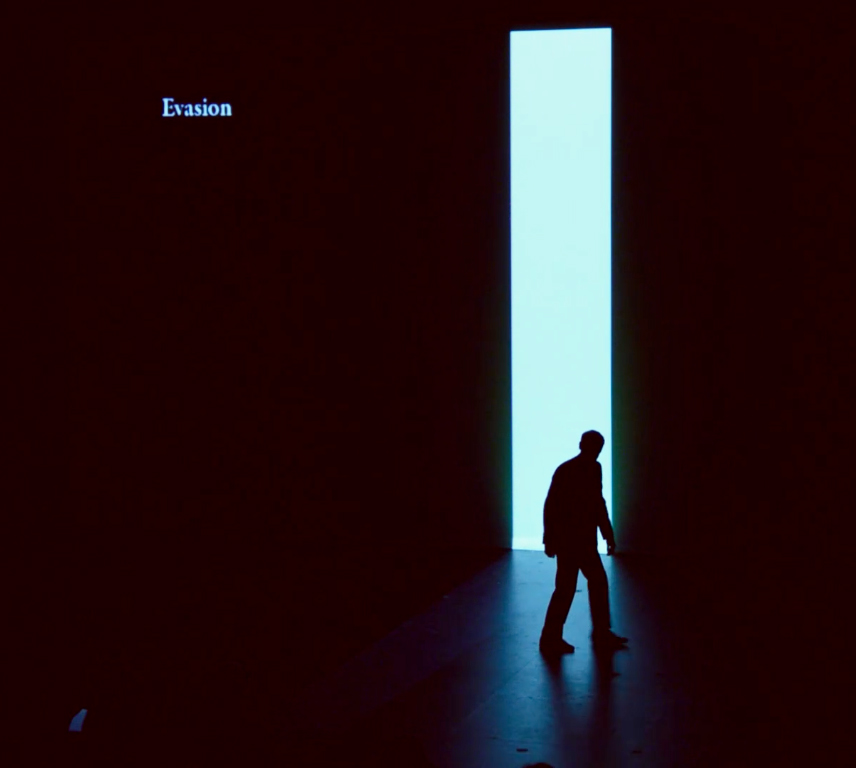

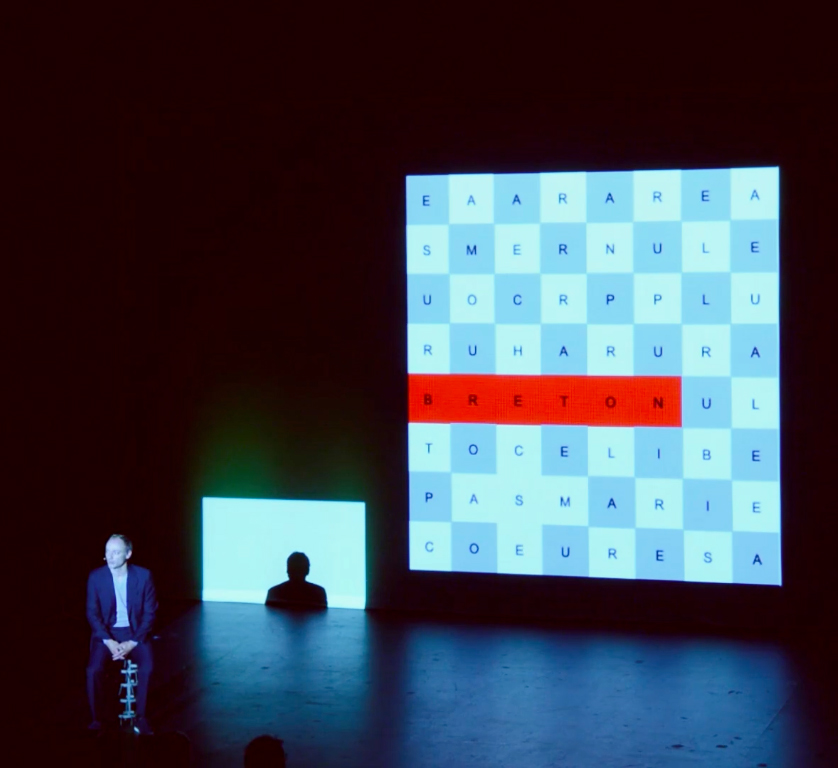

Guillaume Désagnes and Frédéric Cherbœuf

Documentation by Ash Tasnasiychuk for VANDOCUMENT

Copyright © 2012. All Rights Reserved.

Documentation by Ash Tasnasiychuk for VANDOCUMENT

Documentation by Ash Tanasiychuk for VANDOCUMENT

Documentation by Ash Tanasiychuk for VANDOCUMENT

Dustin Brons’s Nauman-inspried potato chip piece.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

re-LIVE Vancouver was a tableau of tribute artworks at VIVO Media Arts Centre on September 25 2011. Installed like a gallery, it became an art exhibition with live art works that were scraping, rubbing, running around, wiggling and jiggling in the corners and along the walls.

Sponsored by the City of Vancouver’s 125th Anniversary Grant Program, it was a reiteration and redistribution of performative creations by some of this city’s most iconic artists. In alphabetical order:

Warren Arcan, Kate Craig, Margaret Dragu, Rodney Graham, Glenn Lewis, Vicent Trasov, and U-J3RK5 (Ian Wallace, Jeff Wall, Rodney Graham –again, Kitty Byrne, Colin Griffiths, Danice McLeod, Frank Ramirez, David Wisdom).

Glenn Lewis and Margaret Dragu were in audience. (Maybe others from that list too, but I wouldn’t have known them.) Kate Craig passed away in 2002, so I am quite sure that she wasn’t there, though a number of women were kind of dressed like her.

How do we do tributes? Why do we re-iterate, repeat, re-imagine, remark, re-play, re-use, repeat, appropriate, re-make, re-stage… ? If we remark on something do we assign it new meaning? If we copy the motions –practice them with our limbs, do we become the past for a moment, or do we ingest them and then finally change their meanings? Who authors the past, when it gets repeated? Derrida said that the original use should not be prioritized over the secondary. In the late 60s Foucault predicted that by now we would be over the author-thing.

Curtis Grahauer’s empty stage was funny. Even though it was a karaoke invitation – the mikes, the music and the words were all in place for us to play and sing along—no one dared to touch the setup, which was meant to exactly mimic the placement of the 8 band members as they were posed on their album cover. The absent rock band. Is anyone counting, how many local tributes have been turned down by the most famed of that crew? (OK forget about them. No one wants to sing along with them anyway.)

Ron Tran’s Peanut, Leopard, Sharks miniaturized the most familiar of performance art props from Vancouver’s early performance art days and put them into the hands and onto the bodies of a pack of preschoolers who were let loose in the gallery for the first couple of hours of the evening. Yes, performance art was a preschooler in Vancouver when these characters were first running and swimming around in circles. The original artists had ridiculous aspirations of taking over the city and the world. (I can imagine them falling down from laughing so hard, just like those kids.) In some ways, Vancouver art has lived up to their impossible international ambitions, of which this show is a reminder. But the reiteration of these works on the bodies of really tiny kids also puts those antics into a kind of disappointing contrast with all of the really smart and serious, institutionally bound, art that gets internationally distributed these days. Only preschoolers have fun now?

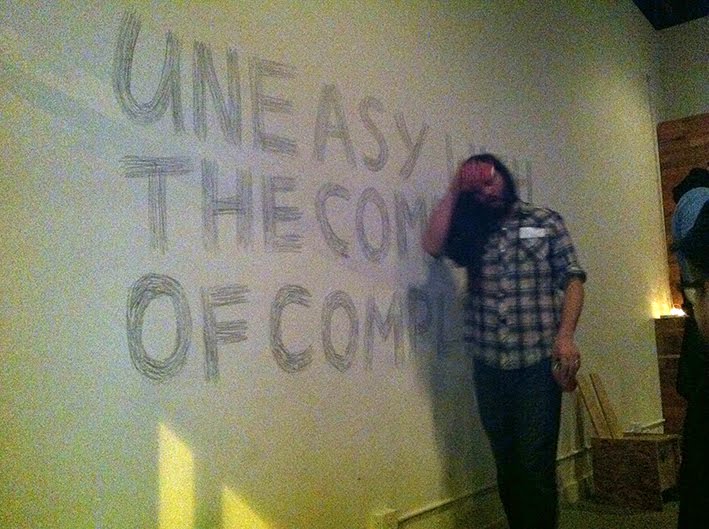

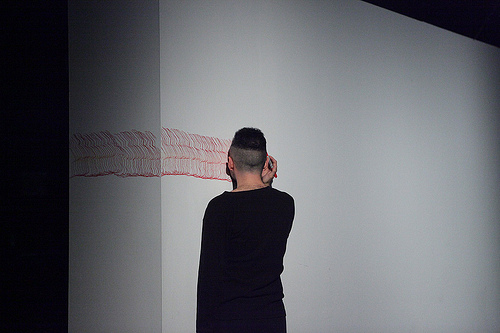

Both Raymond Boisjoly and Francisco-Fernado Granados produced performances by themselves, in front of us, and in response to more senior artists who had also performed at this year’s LIVE. Boisjoy made a simple drawing that spoke back to the overall work of Warren Arcan who had performed Why I am So Beautiful a week earlier in the same venue (VIVO Media Arts Centre). Boisjoly and I talked about Arcan’s particular interest in using worn and familiar materials to work out fantastically intense psychological meanings. In Why I am So Beautiful Arcan used every objects from his mysterious box to speak variations of that beautifully twisted scenario of the love affair. It is complicated, the love affair. The third or the forth or the fifth love affair. First with a stone, then a stuffed bear… then on the phone. Complex, yet comfortable in its familiarity, and increasingly uneasy.

That is only one reading of Boisjoly’s simple gesture of using a beer can to scratch the text,

UNEASY WITH

THE COMFORT

OF COMPLEXITY

onto the gallery wall while everyone partied.

When I read it after he had finished, I was thinking that if the artist knew how many times I uttered the words “its complicated” to newcomers to Canada who didn’t understand things like the government’s abysmal record of unfair dealings with Aboriginal Peoples, he would be uneasy. What do those uneasy words mean?: I can’t take the time to explain that issue to you…or I don’t know the answer but I can’t admit that I don’t know…or I cannot speak….?

Francisco-Fernado Granados’ work was a direct appropriation of a previously performed work by Margaret Dragu. Like a piece of sampled music, he took the smallest of elements from her Western Front performance that is briefly captured here (http://www.livebiennale.ca/1999-2001.html – watch for the tiny clip of Dragu leaving a kiss mark) and repeated it until the surface that he worked against ran out. This work solidified the way that live art was inserted into the gallery form, seemingly a curatorial intention of the re-LIVE Vancouver event. Granados himself has been inserting his intense physical gestures into gallery settings as a way of marking the space with his slowly moving body. His body has been leaving its mark on these revered spaces with materials that belong more on the surface of paper rather than on the body: a red marker in this work, untitled (spatial profiling), or gold gilt (gold in his work is a recurring mark for mourning –of gold mine victims in Guatemala and of a lost lover) as in the recentCrown performance and installation at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre in Vancouver. Margaret Dragu’s participation in Chaos a day earlier for LIVE in the courtyard behind the Firehall Arts Centre was much less about imprinting the body on a cultural or exhibition space, than about working through an evolving series of gestures and materials in a socially evolving context. During Chaos, the audience came and went as four women performers, Sinead O’Donnell, Judith Price, Grace Salez and Margaret Dragu, invented relations with each other, the space and the materials that they had gathered. This was one of those largely generous events during which the audience could ingest a repertoire of actions and reactions that held uncanny fascination and imaginative potential. From a long practice of making those generous Aktions available for her audiences, Dragu’s single kiss mark on the white wall (1999?) was the action that Granados chose to reiterate and practice until he was stained and probably a little sore.

Thank you LIVE 2011 for marking up the city again with new and renewed actions, gestures, forms, poems, songs, texts, uncanny relations…. in such a large and generous display.

Lois Klassen

At the end of the evening, one of Anna Syczewska’s high-heeled shoes, the ones with the 10-inch spikes welded to their soles, remained impaled in the wall. The other lay at the base of the wall where it fell, under the gouged drywall. Her electric wheelchair stood empty, its wheels covered in crushed tomato, the result of its passage over the pile of rotten tomatoes. The tech team had put away the arc-welding equipment and the homemade gynecological stirrups that had held her feet as the professional welded the spikes to the soles of her shoes.

Nothing much clears a room quite as effectively as a 45-minute session of electric arc welding in an enclosed space. The blinding light, the noxious fumes, and the bludgeoning soundtrack pushed the majority of the audience back into the bar or onto the street for some fresh air. Syczewska in her sunglasses sat impassively in her wheelchair tippling from a wine bottle waiting for the slow industrial process to finish.

By the time the spikes on both shoes had been welded in place, it was evident that she had trouble moving her legs. They had remained splayed apart, held in place in her stirrups which would have looked right at home in a clinic run by motor-heads. It was constructed out of three lengths of welded chain, which formed the “Y” and a couple of pieces of bent re-bar that held her feet.

Once the welder completed his painstaking work, the crowd re-entered the gallery space and the show entered another phase. Syczewska stood upright momentarily with the modified shoes. As she balanced precariously, she rubbed a tomato over her legs. Unable to maintain the pose, she collapsed back into the motorized chair.

She maneuvered her chair back away from the audience. Motioning with her hands, she indicated to us that she wanted a path cleared in the rows of chairs. As a way parted in front of her, she revved the chair and moving forward at speed she hit the wall. One shoe remains impaled to this day.

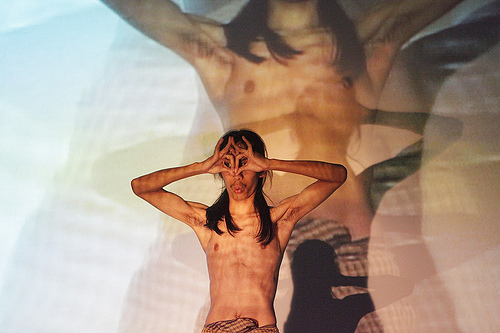

Moe Satt from Yangor Myanmar, presented a simple understated piece. His set consisted of a chair set before a screen. A camera captured both he and the set, and it its image on the screen behind Satt. The positioning of the camera and the video projector were such that it created an infinite repetition of images of Satt on screen, similar to the infinite series of images created by two facing mirrors. In this video version however, the images grew rather than decreasing in size and only the first couple of iterations were visible.

Satt began the show by removing his jacket and shirt. Bare-chested he adjusted the wrap covering his legs, taking care to tie it, in what I imagined to be the traditional manner. Having tied it at the waist he then gathered it up and tied it again to that it covered his genitals and buttocks leaving his legs bare.

He continued by making a number of stylized and symmetric gestures with his hands, positioning them over his eyes, on his face, or over his head. In the audience, we saw these in flesh and blood, as a black shadow projected on to the screen and in the cascading series of video images projected on the screen behind him.

Walking up to the audience he indicated that certain members should mimic him. Satt accompanied these gestures with a whistling of single tones.

At a certain moment, Satt closed the action by walking to the back of the stage, kneeling and bowing.

In analysis Freud spoke of the screen memory. This was a memory, which served to protect the ego from the effects of trauma. It accomplished this by covering the memory of the original trauma with the memory of something else, usually another anodyne event. During analysis the analysand, would return to this harmless memory and to a certain extent this screen memory would come to stand in for original difficult and painful memory.

Anne-Sophie Turion piece recounted a series of childhood memories; a car drive around a lake with the family, a the fragment of a conversation on a telephone, the music her father played on their car drives, the banal exchanges at the family supper table.

The piece began at dinner table set for a party of seven. On the wall behind the set, the Turion’s text and simple stage directions were projected onto the wall. In her halting English, Turion began by telling us that she wished to share a memory with us, but that it was difficult to find the precise memory.

This opened the way to her fragmentary, repetitive and partial description of a number of childhood memories. Interspersed with her narrative she presented the lush musical excerpts that her father enjoyed listening to in some distant past. These included the theme music from the film Jurassic Park, David Bowie, the Doors, and the Hall of the Mountain King.

We never learn of the hidden trauma, or indeed if there were such a thing. There are repeated mentions of her brother and mother but everything is banal to an extreme.

The piece climaxes with Turion climbing up onto the dinner table to lip-sing a song, one of her father’s greatest hits.

It ends as it began with the table reset for seven and Turion repeating her introductory phrases.

We are caught in a neurotic return; never capable of escape from the terrible gravities of a childhood we can never fully recognize and never escape.

Fortner Anderson

It looks like the beginning of a magic show. Black velvety curtains surround an immaculate white plinth, on top of which rests a voluminous glass fish bowl. Pancho emerges, looking a bit like a game show host: red tie, white shirt, and black pants. Some game show-type music comes on the sound system. A water bottle emerges from behind the plinth, he takes a sip.

The show begins. One after another, Coca-Cola bottles emerge from behind the plinth, are opened and emptied into the fishbowl. Empty bottles are neatly lined up in front of the plinth, labels facing forward, and bottle caps are placed on top with equal precision. Lopez is just pouring Coke into a glass bowl, but there is something hilarious about the whole debacle. As yet another bottle appears from behind the plinth, you just have to laugh. Maybe it’s the samba covers of “Smooth Operator” and Prince’s “Kiss” that animate the performance. Maybe it’s the way in which Lopez, completely straight-faced, coyly finds yet another way to pour Coke into the vessel, now over the shoulder, now two at once.

Twenty bottles of Coke transforms the fishbowl into an enigmatic black orb with a pulsing meniscus, threatening to spill at any moment. Twenty-one sends the liquid fizzing over the glass, spilling over the edges of the plinth and onto the floor. Lopez takes a break, pointedly finishing his bottled water as he surveys the squandered bottles of Coke. The final bars of “Smooth Operator” play out. On the last beat of the song, he pulls a baseball bat out of nowhere like a rabbit from a hat and smashes it into the black globe. Glass shards and Coke spatter everywhere. In the heat of the moment, someone throws a chair, barely missing LIVE’s director, Randy Gledhill. Brilliant.

– stacey ho

It was the last instant of Pancho Lopez’s piece Friday night that transformed it from a banal repetitive action to a powerful act of gratuitous poetry. Without that moment when the baseball bat slammed into the overflowing glass vase of Coca-Cola, shattering it into countless pieces sending umpteen liters of coke spilling onto the gallery floor, what would the performance have been?

A man pours liters of coke into a clear glass vase. He arranges the empty bottles in a line and carefully places the red plastic bottle caps along the front edge of the white plinth where the vase sits. Canned music forms the soundtrack. If Lopez had stopped his action before he had filled the vase, taking his bow and walking off stage, I would be writing this post about his commentary on consumption and branding in a modern capitalist society, or perhaps about the ironic and playful gestures he used as he filled the vase with the ugly brown liquid.

At the conclusion of such a hypothetical truncated spectacle, we would have applauded the work nonetheless. If we felt any lingering insatisfaction, we would have attributed it to our incapacity to understand the work’s deeper meanings.

Certainly, the simple act of filling the vase with coke meant something. If we couldn’t we see what it really meant, the cause of our uncertainty would certainly have been our own blindness, our own incapacity to see.

Thankfully, Lopez concluded his piece with an act of irrevocable finality. We no longer need to search for a rational set of meanings to invest within the piece, to explain it or contextualize it, because the beauty and completeness of his act overwhelms those considerations.

Speculations become superfluous and absurd confronted with the poetic act. Of course, its nice to pass the time talking about this and that in relation to a work of performance, but one hopes that during an evening the crystal palace of our rationality will be, for one instant, smashed as an incomprehensible beauty that seizes us by the throat reminding us that life is always something greater than our capacity to understand.

That said, even after such acts of gratuitous poetry, the tech crew still has to come clean up the sticky mess.

– Fortner Anderson

A crowd of at least fifty volunteers met up at Centre A for Lin Yilin’s site-specific performance piece Imagery Knowledge Science. Though I was told I would be totally safe and protected by the gallery staff, I could not help but feel a certain amount of trepidation for what we might encounter.

A crowd of at least fifty volunteers met up at Centre A for Lin Yilin’s site-specific performance piece Imagery Knowledge Science. Though I was told I would be totally safe and protected by the gallery staff, I could not help but feel a certain amount of trepidation for what we might encounter.

We were told that we would be following Lin down some nearby alleys to visit the old telephone poles. At each pole, one of us would read out the profile of a criminal: their height, weight, hair and eye colour, ethnicity, gender, distinctive markings, and so on. Then Lin would climb up a ladder to stick a tiny piece of paper into a crack in the pole. There were thirty-two poles to cover and we did not know what was on the paper. Centre A’s staff informed us there were drug users in these alleys whom we should respect and not photograph.

Following Lin, our group streamed out the door, accompanied by a bevy of community liaisons, traffic controllers, artist assistants, and documentarians for both still and video. Once outside, were were met by more performance enthusiasts and stopped for a quick photo opportunity underneath the gate of Chinatown. Our route would take us down an alley on Carrall St. running parallel between Pender and Hastings. Crossing over Columbia, we would meet a perpendicular alley, travel up towards Hastings, stopping at each pole before turning around and emerging on Pender St., just west of Main.

Our large group almost immediately attracts a police presence, who are easily persuaded that our intentions are artful and therefore harmless. Pretty much everyone else in the alley finds some other place to be.

At the first stop, as a criminal profile is being read, a tiny bird shit falls at Lin Yilin’s feet. At the next, as Lin searches for a crack in the pole, he drops the piece of paper he is hiding. It is yellow, with something grey printed on it. Someone tells me that on the yellow papers are tiny pictures of the people profiled, gathered from North America’s list of most wanted criminals.The first couple profiles are full of descriptions of scars, tattoos, deformities, and bullet marks. I read out one of the few descriptions of a woman:

Height : 5 feet 5 inches

Weight : 133 pounds

Hair : Brown

Eyes : Brown

Hispanic white female

Our slow procession is permeated by the smell of piss on asphalt, marked by a banana peel, dumpsters, pigeons, an abandoned television. Some of our group examine the graffiti plastered on a set of double doors. People take pictures of us from the balconies of some nice looking apartments. We pass the ruins of Vancouver’s first vaudeville theatre, the Pantages, peer in at the crumbed brick, the still-intact proscenium and peach-painted balcony adorned in gold. Some one tells me this space is slated to become another condo. Lin slips a paper in a pole that is also adorned with faded plastic flowers. What the flowers commemorates is mysterious.

The slow pace of our own gathering begins to take on the air of a memorial. In my mind, I liken the anonymous role call to the one given to fallen soldiers. I find myself wondering why the only deserving place to commemorate a criminal is a dirty and piss-soaked alley. My best answer is that this environment, this poverty, is what breeds so-called crime. Perhaps in this environment these profiles represent not soldiers, not criminals, but casualties. Casualties of poverty and also of the rapid development that is overtaking this city.

As we approach the intersection of two alleyways, there is a woman sitting next to a pole who does not want to move or be photographed. A great number of needles are scattered on the ground nearby. Our group discreetly skips this pole. As we pass she begins to moan. Another woman fiddles with a rig as she talks to a friend. With all our cameras, she wants us to take her picture. She tells us this is her space. A man holding a skateboard aggressively tells the crowd, “This is where people get shot, beaten, stabbed. This is where people get happy.” He asks what’s going on. I begin to tell him, but he walks away.

The intimidating size of our group is clearly an issue in this space. I recall that Lin Yilin had initially requested not fifty, but a hundred people for this piece. Of the people who habituate these alleys, a few join us to watch Li Yilin, however many have been surprised at our presence and are acting out. I cannot help but feel that we are embodying the gentrifying force that is rapidly changing this neighbourhood. No matter how mindful or respectful our intentions, the sheer size of our presence is forcing everyone else into change.

Our march concludes and we wander back to Centre A, returning to a familiar world. A class gathers in the library and begins to discuss the performance. People relax on the couches. We are left wondering what our role and the role of art is in the DTES. It is not a new question, but it is one that is perpetually discussed and perpetually unresolved in this city. Lin Yilin’s piece is a harsh but considered contribution to this dialogue.

– stacey ho

Well folks, last night was the first night for Live 2011! An auspicious start to what should prove to be a powerful and fun-filled festival.

Well folks, last night was the first night for Live 2011! An auspicious start to what should prove to be a powerful and fun-filled festival.

Fortner Anderson kicked things off, reciting the long poem, “Drifting into Fire”. The piece is one of three from a cycle called “Annunciations”, which each stem from investigative reports of modern disasters. Drawing from NASA’s accident report on the Space Shuttle Columbia, Anderson’s dynamic delivery shifted rapidly between ecstatic and mechanistic. At the most intense points of Anderson’s performance, it felt as if words were being forced from his mouth, like they could barely squeeze themselves out. Fitting, given that his subject is catastrophe at a scale that is at the very limits of what we can express or fathom. By truly considering the details outlined in these reports, Anderson saves these contemporary events from dry factuality. Our collective experience of tragedy takes on the feeling and gravity of something closer to Blake instead of the numbness of a newsfeed.

Following was Dana Claxton performing The Elsewhere with the help of Sam Bell. Central to this piece was a vessel made of hide, brightly painted with a long fringe at the bottom. Sam, who has collaborated with Claxton on several films, mentioned later that Claxton has a collection of such special objects. Despite the predominant position given to this beautiful container, it remained untouched for the majority of the performance. Instead a delicately balanced space was slowly built around the object, using stones, gestures and sound.

The piece proceeded in a gratifying 4/4 time, with Claxton moving backwards, eyes shielded from sight. Four bags of large grey stones were emptied on the floor. Four pairs of stones were each struck four times and laid out to make four paths radiating from the centre of the space. Four new bags of rocks were each dropped four times, the gesture creating a forceful and heavy sound, then emptied on the floor. Polished stones were revealed in red, black, pale yellow and white.

When Claxton finally approached the container, she began for the first time to move forward, circling the room and shaking the vessel so its contents rattled. A final action, the container’s contents were poured out in the centre of the room, revealing rainbow-hued abalone shells and handfuls of turquoise. Surprise at the sudden unveiling of this colourful bounty. A song is played on the stereo, traditional, aboriginal, female, and the audience is invited to take with them a “token of mother earth”. We are left with a gift of beauty.

This place, this Elsewhere that Claxton created last night, conveyed a specific conception of space, an ‘Indianized’ space. The materials and structure of her piece invoke a space that is organic, natural, harmonious. By offering us the materials of her piece, she implies a space that can shift and travel, as well as a space of sharing.

Claxton’s performance was nicely balanced by the cheeky humour of Jean Dupuy, who presented three pieces in sound and video. In B. versus B., a ‘stuttering’ author plays Beethoven’s Sonata #9 and Brahms’ Sonata #3 out of two separate speakers as images of the venerable composers slowly revolve on two back-to-back laptops placed on the floor. Not only were the two poor B.’s pitted against each other, but they also had to face the trial of presentation through digital technology. Some (unintentional?) audio glitches added to the stutter of the piece. Brahms’ gaze remained sulkily fixed on the mouse cursor that graced the laptop screen.

Next, a performance with the lighthearted spirit of Chaplin, preserved on 16mm film. Shot in 1976 from a bird’s-eye view, Dupuy and his wife stride towards each other in the middle of the street. They meet in the centre of an intersection and embrace. The camera zooms as they strip and exchange clothes. She has big, light yellow undies; I think his drawers are black. They fumble around a bit, dress, and as a final touch, exchange eyeglasses. Arms around each other’s waist, they walk merrily down the street. The couple turn a corner, and are gone. Simple and charming.

The final piece was a sound work of the train from Paris to Bordeaux, at the time the fastest train in France. Recorded using the train’s toilet bowl to amplify the sound, the Western Front’s audience was treated to fifteen minutes of this hours long piece. Dupuy recommended that the audience lie on the floor to enjoy the vibrations from the sound waves. Some dutifully complied though others were put off by a warning that the sound would be very loud. Despite this notice, when I laid down I found the irregular yet repetitive overtones of the moving train acted as a sedative to my prone mind and body. As I enjoyed the calming effect of these mild tremors across my back and legs, I distinctly felt the footsteps of people quietly exiting the room, bringing to a close the first night of the Biennale.

– stacey