Some closing remarks

By Stacey Ho

It’s October (Oh god. It’s November.) already and still the dust is settling after LIVE 2013. That week flew by: a flurry of art and artists, of late night meals and intense discussion, of last-minute changes and spontaneous decisions. What fun to take part! As a newfound excitement around the medium of performance continues to gain momentum, LIVE intends to direct this energy towards facilitating greater discourse around performance art and the development of performance-based practices, expanding platforms for presenting the performance medium, and connecting the concerns of performance with wider dialogues in contemporary and visual art. Looking back, there is also much to look forward to and work towards.

1.

This year’s program served to inaugurate a few new ideas that have been bouncing around LIVE for quite some time, one being a greater focus on processes and pedagogy, on practices over end results. Parenthetically, I saw some similar ideas articulated in the piece “Trail of Love” presented by Lori Blondeau, which closed the first evening of LIVE’s performances. Working through the day, Blondeau methodically outlined figures based on aboriginal petroglyphs in red, white, yellow, and pink rose petals. The atmosphere was causal, with friends helping, music playing, audience members drifting in and out of VIVO, an opened bottle of wine displayed on the floor. LIVE’s designer, Walter Scott, called it “a girls’ night out”, totally, but as Blondeau glued on the petals that formed the last figure, I felt what I was really privy to was an artist at work as a work of art.

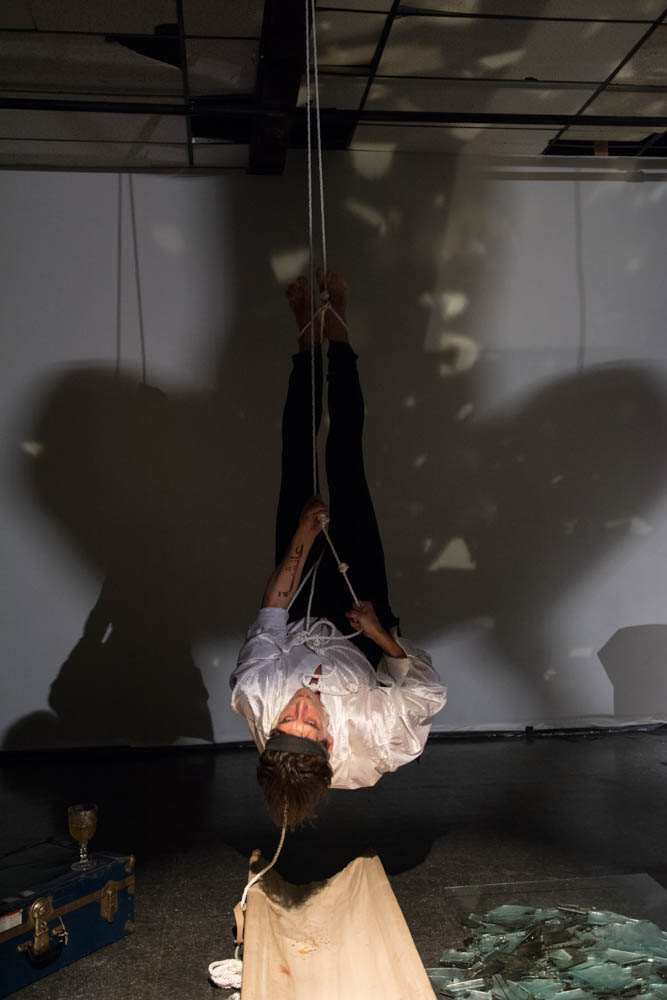

LIVE’s program addressed art practices in more direct terms as well through the performance art workshop led by Black Market International co-founder Jürgen Fritz. This was a physically intensive four-day endeavour, culminating in a two-hour group performance by workshop participants. “Exploring Performance Art” is the first in a series of upcoming residencies and workshops that will serve as a means of introducing art practitioners to rigorous ideas on performance and generating sustained, meaningful dialogue around the medium within the context of Vancouver. I see these programs as an extension of the Retreat organized by LIVE in 2012, a co-ordination meeting between performance art organizations, the results of which are just now being published. Both are a means for LIVE to go beyond the simple presentation of performance art, ensuring that the medium is developed and promoted with intention both regionally and globally.

2.

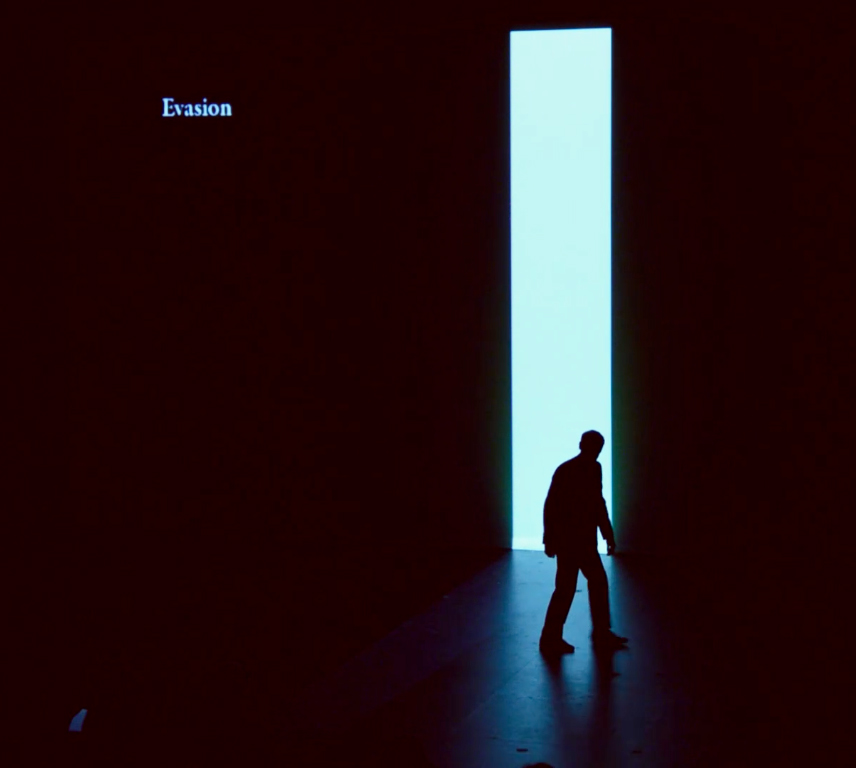

I would argue that more than any other medium, performance—gestures, interventions, and art actions—has the potential to move beyond the formal concerns of art—the white box of the gallery, the black box of theatre—and touch upon the real. In this respect, the most challenging piece I witnessed this year was Jelili Atiku’s street performance, where, stripped down and painted gaudy blue, Atiku dragged bundles of clothes chained together with strips of cloth along Hastings St. in Vancouver. Though volunteers helped him with this task, Atiku shouldered much of this soaked and heavy burden on his own. He laid out on the sidewalk. He handed oranges out on the street. The performance respectfully brought to mind the meaning of inserting one’s own experience, coming from a parallel context of marginalization, into the DTES.

By consistently commissioning art that engages audiences outside of the gallery and curating work by artists from so-called developing nations, LIVE continues to facilitate the exploration of boundaries between place, audience, situation. Another instance: Macarena Perich-Rosas’ idiosyncratic magnetism as she beautifully conveyed an impression of Patagonia, her home “at the end of the world”. Rosas’ performance alluded to regionalism through strange and simple objects: yerba matte tea, woolly sheep hides, chamomile cream, traditional boina berets. At her artist talk the next day, I could not help but picture her action of precariously tightrope-walking along a cirrus cloud of cotton balls as she spoke of her isolated, challenging, and windy home as a specific counterpoint to the totalizing influence of globalization and the corresponding, homogenizing tendencies of contemporary art.

(Tangentially, I am also thinking of LIVE board member Emilio Rojas‘ practice of “Identity Crossing”, where he traverses the US border cloaked as various hyperreal fantasy images of the Mexican immigrant—in tropical garb and silver wrestling mask; with head and face half-shaved; as a Mexican charro in cowboy hat. Rojas’ action is unannounced, sometimes undocumented, enacted more for the border patrol than for a fine art audience.)

Frames and white boxes are not only spatial but also temporal… Though the practice is decades old, durational performance remains a challenge to art audiences, calling attention to the passage of time in ways that cannot be easily consumed. During LIVE, I was surprised to observe that many people still do not know what to make of durational work and tend to discount that which does not instantly gratify. It bothered me that Alain-Martin Richard’s subtle manoeuvres, slow as a melting ice cap, often slipped by unnoticed. Richard’s performance was a microcosm of world catastrophe: a communion between himself and a block of ice with potatoes, corn, grains, rice—the staple foods of the world—frozen into it. It bothered me too that when Snežana Golubović unravelled a riveting-red handmade dress from her body, she only had time to shorten the length of it up to her ankles: the standard half- to one-hour time allotment typical to the presentation of performance art was not sufficient. Really, a wealth of time- and performance-based work does not fit such temporal constraints, nor should it have to. In our programming, LIVE must further address how to afford sufficient time and space to such meditative, often understated pieces, so that viewers may give them the weight and attention that they require.

3.

The fun thing about helping out with LIVE is getting to take in the whole endeavour, witnessing each artist as a singular intelligence swept up in a heterogenous katamari ball that comes from all angles to address the present moment. A few final, disparate impressions:

In that oddly contemporary genre of ‘performance art that retells historic performance pieces by redoing them’, Dustin Brons’ careful echoing of Bruce Nauman’s “Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square” was amongst the most successful I’ve encountered. The replacement of Nauman’s masking tape with Pringles, ordered single-file, added a humorous and delicate pop-culture crunch to the tribute. Infused with Brons’ awkwardly charming presence rather than Nauman’s sashay, the execution was still close enough to the original to feel true to its reference…

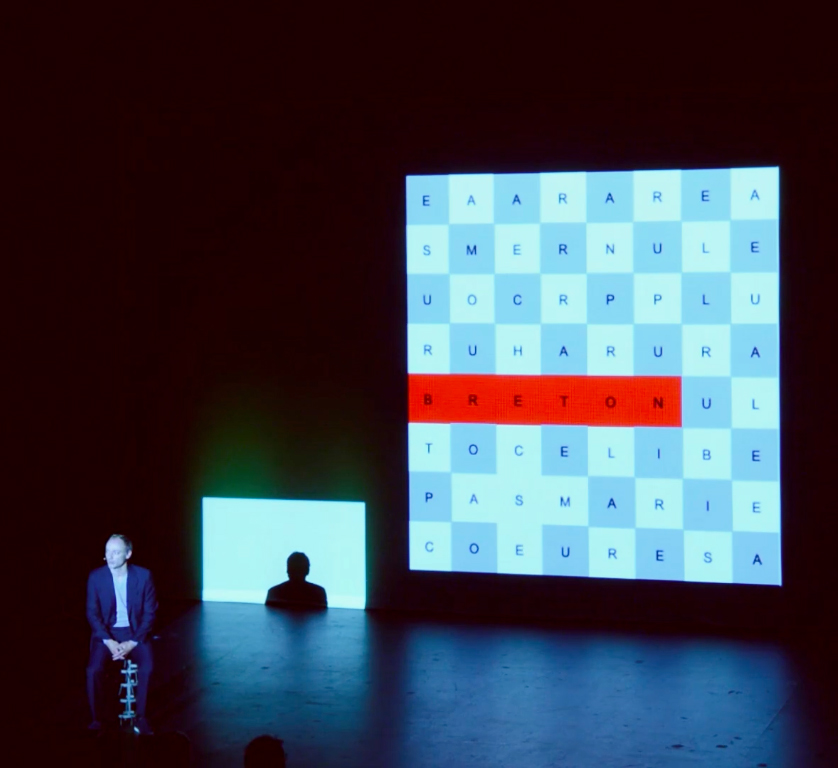

Certainly, performance art addresses the body. Less common is to approach the subject from the perspective of not only art, but also biological science: a field where what remains to be discovered lies largely in the mind. Half freewheeling pop neurology lecture, half schoolyard playfight, Márcio Carvalho’s “Power over Memory” reenacted the war-like gestures of boyhood using video games, water guns, wind-up toys, and fireworks. Drawing parallels between the memory loss of action hero John Rambo and musicologist Clive Wearing, Carvalho questioned how and who forms our collective memory, a reminder that perhaps we too are trapped in a repeating present, brought on by a forgetfulness that is systemic and habituated…

Meanwhile, eschewing the art world to kick off karaoke night at Pat’s Pub and Brewhouse, a semi-serious, funny-as-hell set by Donato Mancini and Gabriel Saloman somehow simultaneously straddled the line between angst-ridden onomatopoeic poetry reading, Suicide-era noise gig, and stand-up comedy routine… Their strung-out energy got me nerdily excited about schizophrenic-pluralistic art-making approaches, the blending of performance art with poetry, with dance, with music and media, with the ideas brought up through the festival on politics and place, art and science, historical research and critical theory. LIVE is ready to bring all of this into the discussion. (Without losing sight, of course, of the qualities that make performance theoretically challenging and inherently radical: its fundamental humanity, in that its subject is inescapably the body and the being of the maker; its intrinsic ephemerality, so that through the performative gesture, the art object is eviscerated. So that what remains is not concept, but an experience.)