Video: VestAndPage

Puppets and pantyhose. Blood, balloons, and broken glass.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

Copyright © 2012. All Rights Reserved.

Puppets and pantyhose. Blood, balloons, and broken glass.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

Jason Lim’s moving response to his visit to Vancouver.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

Luciana D’Anunciacao presents her gorgeous performance piece ‘Banho’ for LIVE 2013.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

Dustin Brons’s Nauman-inspried potato chip piece.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

Lori Blondeau, drawing with roses.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

I arrived at the courtyard of the Firehall Arts Centre around 11:20 Saturday morning. The four-hour durational performance by Margaret Dragu, Grace Salez, Judith Price and Sinéad O’Donnell had begun at 11 and was already in full swing.

The performance of these four women was quite different from those of Pancho Lopez or Christian Messier, which had taken place earlier in the festival program. The performances of both Lopez and Messier led their audience toward a single climactic moment, a surprise that revealed the logic and beauty of their action. Lopez smashed the vase full of Coca-Cola with his baseball bat; Messier opened his mouth and from it billowed a cloud of white dust.

The whole arc of their respective performances had led to that one moment. The actualization of these poetic images completed their pieces. Once revealed, any further performance was pointless.

The actions of the four women were of a different order. There was no arc towards climax. Composed of hundreds of actions and images, their performance continued throughout the afternoon. They worked through a few simple actions, which were repeated constantly, always with a slight variation, with a few new events occurring throughout the day.

Four hours is a long time to create a performance with a coherent conceptual framework. For this slow organic process of creation to succeed in engaging the public, the performers must work with an intense focus. Their individual acts throughout the period must have a poetic resonance, they must be coherent within a concept, and they must show some development. It’s a very difficult act to pull off.

Their show was called “Chaos”. Though the women worked in disparate realms, interacting only rarely, the over all feeling of the piece was, for me, not one of the world out-of-order. There was no violence, no anxiety or terror that I associate with a world gone amok. On the contrary I felt that these women were working to create some kind of order from a primeval and formless state.

Throughout the day Grace Salez remained blindfolded. She alternatively pushed and pulled a wheelbarrow full of rotten apples, walking a few halting steps from one side the courtyard to the other. Judith Price lay on a picnic table and struggled to climb out from a felt bag. Sinéad O’Donnell with a painted face, her dress stained red and covered with Vaseline and flour, walked dazed around the central tree placing small black ravens here and there. A whole dead fish lay on a bed of ice. Margaret Dragu sat ensconced on the deck over looking the courtyard. On a small table she had set-up her mending station with a tin of buttons, her sewing supplies, a few articles of clothing that needed care.

Each of the women created a unique space with a separate gravity and logic, which she developed throughout the day with a hundred slight variations. Turning your head from one performer to another, the eye was constantly caught anew by striking images: Judith cutting her toenails and covering her bare feet with band aids, Dragu singing karaoke version of “The Days of Wine and Roses” with her clients, O’Donnell, her hand stuffed into a loaf of bread biting off chunks and eating, and Grace always moving gingerly, her hands searching the space before her seeking something solid.

It is unfortunate that so few members of the Live audience came by to see this performance. It was a solid cascade of poetic images that rained down without cease. In one short afternoon, a lucky few witnessed absurd, tragic, motherly forces wrest form from nothingness.

Fortner Anderson

At the end of the evening, one of Anna Syczewska’s high-heeled shoes, the ones with the 10-inch spikes welded to their soles, remained impaled in the wall. The other lay at the base of the wall where it fell, under the gouged drywall. Her electric wheelchair stood empty, its wheels covered in crushed tomato, the result of its passage over the pile of rotten tomatoes. The tech team had put away the arc-welding equipment and the homemade gynecological stirrups that had held her feet as the professional welded the spikes to the soles of her shoes.

Nothing much clears a room quite as effectively as a 45-minute session of electric arc welding in an enclosed space. The blinding light, the noxious fumes, and the bludgeoning soundtrack pushed the majority of the audience back into the bar or onto the street for some fresh air. Syczewska in her sunglasses sat impassively in her wheelchair tippling from a wine bottle waiting for the slow industrial process to finish.

By the time the spikes on both shoes had been welded in place, it was evident that she had trouble moving her legs. They had remained splayed apart, held in place in her stirrups which would have looked right at home in a clinic run by motor-heads. It was constructed out of three lengths of welded chain, which formed the “Y” and a couple of pieces of bent re-bar that held her feet.

Once the welder completed his painstaking work, the crowd re-entered the gallery space and the show entered another phase. Syczewska stood upright momentarily with the modified shoes. As she balanced precariously, she rubbed a tomato over her legs. Unable to maintain the pose, she collapsed back into the motorized chair.

She maneuvered her chair back away from the audience. Motioning with her hands, she indicated to us that she wanted a path cleared in the rows of chairs. As a way parted in front of her, she revved the chair and moving forward at speed she hit the wall. One shoe remains impaled to this day.

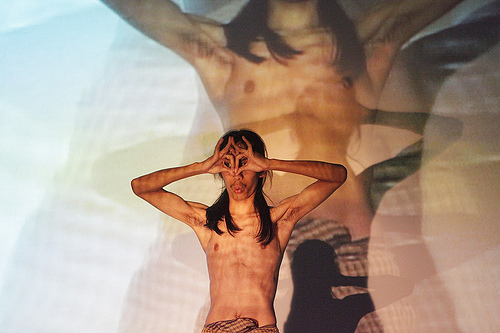

Moe Satt from Yangor Myanmar, presented a simple understated piece. His set consisted of a chair set before a screen. A camera captured both he and the set, and it its image on the screen behind Satt. The positioning of the camera and the video projector were such that it created an infinite repetition of images of Satt on screen, similar to the infinite series of images created by two facing mirrors. In this video version however, the images grew rather than decreasing in size and only the first couple of iterations were visible.

Satt began the show by removing his jacket and shirt. Bare-chested he adjusted the wrap covering his legs, taking care to tie it, in what I imagined to be the traditional manner. Having tied it at the waist he then gathered it up and tied it again to that it covered his genitals and buttocks leaving his legs bare.

He continued by making a number of stylized and symmetric gestures with his hands, positioning them over his eyes, on his face, or over his head. In the audience, we saw these in flesh and blood, as a black shadow projected on to the screen and in the cascading series of video images projected on the screen behind him.

Walking up to the audience he indicated that certain members should mimic him. Satt accompanied these gestures with a whistling of single tones.

At a certain moment, Satt closed the action by walking to the back of the stage, kneeling and bowing.

In analysis Freud spoke of the screen memory. This was a memory, which served to protect the ego from the effects of trauma. It accomplished this by covering the memory of the original trauma with the memory of something else, usually another anodyne event. During analysis the analysand, would return to this harmless memory and to a certain extent this screen memory would come to stand in for original difficult and painful memory.

Anne-Sophie Turion piece recounted a series of childhood memories; a car drive around a lake with the family, a the fragment of a conversation on a telephone, the music her father played on their car drives, the banal exchanges at the family supper table.

The piece began at dinner table set for a party of seven. On the wall behind the set, the Turion’s text and simple stage directions were projected onto the wall. In her halting English, Turion began by telling us that she wished to share a memory with us, but that it was difficult to find the precise memory.

This opened the way to her fragmentary, repetitive and partial description of a number of childhood memories. Interspersed with her narrative she presented the lush musical excerpts that her father enjoyed listening to in some distant past. These included the theme music from the film Jurassic Park, David Bowie, the Doors, and the Hall of the Mountain King.

We never learn of the hidden trauma, or indeed if there were such a thing. There are repeated mentions of her brother and mother but everything is banal to an extreme.

The piece climaxes with Turion climbing up onto the dinner table to lip-sing a song, one of her father’s greatest hits.

It ends as it began with the table reset for seven and Turion repeating her introductory phrases.

We are caught in a neurotic return; never capable of escape from the terrible gravities of a childhood we can never fully recognize and never escape.

Fortner Anderson

On night three of the festival, the programming changed gears again. We’re no longer carefree youth joy-riding up East Hastings playing air guitar and singing along to our favorite pop tunes in our parent’s SUV, tonight we’re in a 16 wheel tractor trailer pulling a impossibly dense load of fissionable material, the diesel engine whines as we down-shift to gain traction on the rise up Main Street on our way to the Vivo Gallery. Our drivers, Christian Messier from Quebec City, Him Lo from Hong Kong and Warren Arcan from Galiano Island, have turned deadly serious, and intend to take us places–beautiful, violent and heartbreaking places.

Christian Messier started the evening with his slow construction of a single moment, a vision of evanescent beauty that captured the frailty and absurdity of the human project. Him Lo took us into the deep id as witnesses to the violent tectonic movements of familial relationships and crushing depression. Warren Arcan concluded the evening with a magisterial, urbane, droll and heartfelt exposition of love, in its carnal and spiritual forms.

Fistful by fistful Christian Messier covered himself with flour, first his shoes, then pants, shirt and finally his face and hair. He then took two large packages of clay from off stage. The first he unwrapped and slowly molded it into a pile on the floor, which he stepped onto. The second he placed on his flour dusted head. Handful by handful he continuously pulled the clay down onto his forehead and ears. Clods fell to earth at his feet.

As the mass of clay on his head grew smaller, a figure emerged. As he tore away the last clods of clay, it became apparent that this was a roughly carved figure of a human form, a fetish.

Christian held this small figure in his two hands at his chest and at that moment spewed a cloud of flour from his mouth. The white cloud of dust billowed and shone in the light, but only for a moment before it dissipated and fell to earth.

This beautiful fleeting shock concluded the piece.

After a 30-minute break, to clean up the mess and socialize in the Vivo lounge, we entered the gallery to the second set-up, the performance by Him Lo. In the centre of the gallery a large piece of canvas had been taped to the floor. From the ceiling hung a large painter’s drop cloth covered in the paint spills of dozens and dozens of jobs. On the canvas in the centre of the floor stood a jet-black man wearing dress pants, white shirt and tie. In his hands he held a mop and at his feet was an enameled bowl containing a white liquid that I later learned was glue.

The show started with the lights turned down. A series of simple pencil drawings were projected onto the cloth. A playback of Him Lo’s voice told us of “a man, a woman, a fusion, and a child”. The black man used the mop to cover the canvas with the glue. When he emptied the bowl of glue onto the canvas he tossed it aside and from the rear of the room an assistant tossed out a soccer ball.

Him began kicking the ball violently against the drop-cloth screen where the images of the family were projected. Again and again with a startling violence Him Lo kicked the ball toward the screen. Slipping in the glue covered canvas, and falling with such force I felt sure he’d snapped an ankle. This continued as the sound track spoke of the family, the family the family.

This continued to exhaustion. Him Lo concluded the piece telling us that the piece was dedicated to his father.

After a second break we came back to Warren Arcans’s performance. Warren introduced his piece with an informal presentation of himself. He felt it would be useful to present his “baseline” personality before the performance so that we could more easily determine the frontiers between the performance and life.

The scene was simple, a small table, a chair, a telephone and a cardboard box containing several props. As Warren started, an assistant picked up a boom mic and held it above him, as if in a film shoot. The sound picked-up was amplified to the room.

From his cardboard box Warren took a container of gravel and spilled it onto the table. He leaned close the small pile and began to address the rocks. He began to seduce them, speaking in the discourse reserved for new lovers, who in the most intimate of moments, as love blooms try to discover the other and expose to them their singularity.

The cardboard also held a skull of some long toothed beast and a plush toy, these and a real dog provided Warren a foil for his exposition of the facets of love. Desire, loss, jealousy. The objects, which become love-objects and Warren convinces us that he is speaking his heart to his small floppy-eared teddy.

Warren also talks directly to god, the prime mover ruminating as to why their love has failed; perhaps it’s a lack of trust.

The piece concludes with a phone call, presumably to a former love. Using the speakerphone, we understand that there is no one at the other end of the line only the occasional room noise responds to Warren’s heartbreaking realization that their love is no longer possible.

A dial tone indicates any further attempt at dialogue is useless and the piece ends.

– Fortner Anderson

Well folks, last night was the first night for Live 2011! An auspicious start to what should prove to be a powerful and fun-filled festival.

Well folks, last night was the first night for Live 2011! An auspicious start to what should prove to be a powerful and fun-filled festival.

Fortner Anderson kicked things off, reciting the long poem, “Drifting into Fire”. The piece is one of three from a cycle called “Annunciations”, which each stem from investigative reports of modern disasters. Drawing from NASA’s accident report on the Space Shuttle Columbia, Anderson’s dynamic delivery shifted rapidly between ecstatic and mechanistic. At the most intense points of Anderson’s performance, it felt as if words were being forced from his mouth, like they could barely squeeze themselves out. Fitting, given that his subject is catastrophe at a scale that is at the very limits of what we can express or fathom. By truly considering the details outlined in these reports, Anderson saves these contemporary events from dry factuality. Our collective experience of tragedy takes on the feeling and gravity of something closer to Blake instead of the numbness of a newsfeed.

Following was Dana Claxton performing The Elsewhere with the help of Sam Bell. Central to this piece was a vessel made of hide, brightly painted with a long fringe at the bottom. Sam, who has collaborated with Claxton on several films, mentioned later that Claxton has a collection of such special objects. Despite the predominant position given to this beautiful container, it remained untouched for the majority of the performance. Instead a delicately balanced space was slowly built around the object, using stones, gestures and sound.

The piece proceeded in a gratifying 4/4 time, with Claxton moving backwards, eyes shielded from sight. Four bags of large grey stones were emptied on the floor. Four pairs of stones were each struck four times and laid out to make four paths radiating from the centre of the space. Four new bags of rocks were each dropped four times, the gesture creating a forceful and heavy sound, then emptied on the floor. Polished stones were revealed in red, black, pale yellow and white.

When Claxton finally approached the container, she began for the first time to move forward, circling the room and shaking the vessel so its contents rattled. A final action, the container’s contents were poured out in the centre of the room, revealing rainbow-hued abalone shells and handfuls of turquoise. Surprise at the sudden unveiling of this colourful bounty. A song is played on the stereo, traditional, aboriginal, female, and the audience is invited to take with them a “token of mother earth”. We are left with a gift of beauty.

This place, this Elsewhere that Claxton created last night, conveyed a specific conception of space, an ‘Indianized’ space. The materials and structure of her piece invoke a space that is organic, natural, harmonious. By offering us the materials of her piece, she implies a space that can shift and travel, as well as a space of sharing.

Claxton’s performance was nicely balanced by the cheeky humour of Jean Dupuy, who presented three pieces in sound and video. In B. versus B., a ‘stuttering’ author plays Beethoven’s Sonata #9 and Brahms’ Sonata #3 out of two separate speakers as images of the venerable composers slowly revolve on two back-to-back laptops placed on the floor. Not only were the two poor B.’s pitted against each other, but they also had to face the trial of presentation through digital technology. Some (unintentional?) audio glitches added to the stutter of the piece. Brahms’ gaze remained sulkily fixed on the mouse cursor that graced the laptop screen.

Next, a performance with the lighthearted spirit of Chaplin, preserved on 16mm film. Shot in 1976 from a bird’s-eye view, Dupuy and his wife stride towards each other in the middle of the street. They meet in the centre of an intersection and embrace. The camera zooms as they strip and exchange clothes. She has big, light yellow undies; I think his drawers are black. They fumble around a bit, dress, and as a final touch, exchange eyeglasses. Arms around each other’s waist, they walk merrily down the street. The couple turn a corner, and are gone. Simple and charming.

The final piece was a sound work of the train from Paris to Bordeaux, at the time the fastest train in France. Recorded using the train’s toilet bowl to amplify the sound, the Western Front’s audience was treated to fifteen minutes of this hours long piece. Dupuy recommended that the audience lie on the floor to enjoy the vibrations from the sound waves. Some dutifully complied though others were put off by a warning that the sound would be very loud. Despite this notice, when I laid down I found the irregular yet repetitive overtones of the moving train acted as a sedative to my prone mind and body. As I enjoyed the calming effect of these mild tremors across my back and legs, I distinctly felt the footsteps of people quietly exiting the room, bringing to a close the first night of the Biennale.

– stacey