Guadalupe Neves

Documentation by Ash Tanasiychuk for VANDOCUMENT

Copyright © 2012. All Rights Reserved.

Documentation by Ash Tanasiychuk for VANDOCUMENT

Documentation by Ash Tanasiychuk and and Faber Neifer for VANDOCUMENT

LeanneJ + My Name is Scot’s guerrilla poetry intervention in Vancouver’s Victory Square

Sept. 21 2013

Photos by Jürgen Fritz

Macarena Perich-Rosas plays with symbols of Patagonian masculinity.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

Alain-Martin Richard’s communion with ice

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

By: Jacquelyn Ross Written On: September 30, 2013

LIVE Biennale @ VIVO Media Arts Centre, Thursday September 19, 2013.

Snežana Golubović, Márcio Carvalho, Steve Hubert

This article is published in collaboration with Decoy Magazine.

–

Memoirs of a Lasting Sting

I cannot deny that I generally approach performance art with some hesitation. Whether it is a hesitation to engage with the theatricality of a performance’s proposition, its relentless duration, or the expectations and obligations placed on the viewer to perform alongside it, for me, the hesitation that haunts the discipline is, at its core, rooted in a deep skepticism of authenticity. Without doubt, I am a product of my times. I was born almost thirty years after the revelations of The Gutenberg Galaxy, in the year that CDs out-sold vinyl records for the first time. I don’t need a performance to give me ‘the real thing’, or trigger nostalgia about a past that isn’t mine. Instead, I am captivated by the materials of the present, and the urgent and exhilarating project of creating with the cards at hand. Like beachcombing for engagement rings lost in the sand, or for Japanese debris on the west coast (which continue to prove that the world is both vast and communal), I want to know what transcendent act might deliver us into our own times. In the spirit of the Tupac hologram and the technological ghost of a lost rapper, what I really want, in my own way, is to be transported.

What I have learned at LIVE is that performance art doesn’t have to be boring. In fact, the evening presented a wide spectrum of works that showcased exactly the type of sea change that I may have been waiting for. With the exception of the lacklustre opening performance by Serbian based Snežana Golubović—in which the artist apathetically unraveled a long, knitted, cerise tube top to the impatient tapping of a metronome—the evening ensued with pronounced distance from the kind of Abramović-school ‘Performance Art’ that I had been dreading. Instead, a younger generation of artists presented works that could be defined as performance art because something was being performed, albeit irreverently, informally, and ironically. Here, performance was reframed as a proposition, where spectacular events unfolded somewhere between a university lecture, a cold reading, a cooking demo and an indie music show. When asked by a friend what I thought of the event, I could only describe it as “spectacularly provisional”. Props, clunky multi-media tricks, schizophrenic characters, esoteric scripts and obtuse narratives combined to recreate what I consider to be the spectacle of contemporary life, colliding with the irony of its makeshift construction. In contrast to the kind of sincerely provisional and essentialist body politics of Yoko Ono or Chris Burden, performance art today can be excessive, intemperate and unapologetically entertaining. The shift is palpable.

Márcio Carvalho. “Power Over Memory—A Case Study” performance, 2013. Photo credit: Faber Neifer, VANDOCUMENT.

Sporting a water gun, blue jeans and tight Hawaiian shirt, the trim beach-bod of Portuguese artist Márcio Carvalho is an able subject for the physical exercises enacted in his exploration of memory and the body. Hailing from the sunny scenic fishing town of Lagos, in Portugal’s southern Algarve region, he provoked a memory which was already at play for me even before the performance began, remembering Lagos from the happy accident of its discovery during my travels in 2007. Impossibly photogenic, the town’s sleepy charm is coupled by its breathtaking beaches: geological marvels with staggering tawny cliffs of layered sediment, and reclusive caves that fold into the rock faces like coat pockets. It is through the metaphor of those Lagosian cliffs that I enjoyed Carvalho’s audacious and even cheeky performances, which mine the absurd strata of the brain and its capacity for memory, emotion, and logic. The innocence of his encounter was boyishly profound. In the style of a live instructional video, Power Over Memory—A Case Study compared the fictional hero John Rambo with the amnesiac Clive Wearing, as two seemingly disparate examples of characters unable to retain and consolidate memory. Crude diagrams, Wikipedia facts and footnotes supported a series of experiments investigating this problem, as the artist embodied Rambo and Wearing’s polarized archetypes to stage false threats and heroic rescues, create surprising ruptures in time and space, and displace self-assured notions of identity and self-control.

Onwards down the rabbit hole, Vancouver based artist Steve Hubert’s performance offered simulacra everywhere, appearing more real than the real. In The Scorpion’s Poem, the recurring motif of the scorpion acted out over and over again as both threat and promise: with its palm-sized body and poison sting, it is the phallic lobster, desert arachnid, king of the subterrain. A childish plot followed the story of a naïve girl in search of a companion as she roamed the tired aisles of a pet store, only to be persuaded that the scorpion would be the best fit for her needs and budget. Chaos ensued as a series of semi-coherent jump cuts, flashbacks and songs propelled the narrative forwards and backwards, extending the vocabulary of film to the arena of live theatre, installation, video and performance. Meanwhile, Hubert was masterminding the production’s multi-media operation from his inverse lounge chair: a makeshift scorpion-shaped structure salvaged out of scrap wood and screws that reaffirmed the artist to be the omnipresent narrator and meta-creator of the work. In a galaxy as flat as a Google image search and as deep as its improvised projection screen, stage cues were read aloud, while a glowing green terrarium remained suspended, in waiting. These were some of the magic ingredients that made up the micro- and macro-narratives of Hubert’s elaborate world. The audience watched in anticipation while the actors attended to each detail of their intricate environment—whether it was the props, cues, lighting, or sound—creating a hyper-real stage, sustained by the collective faith and confidence of its singular inhabitants, and buffered from the cynical effects of the outside world.

Steve Hubert, Scorpion Control Centre in studio with works in progress, 2013. Image courtesy of the artist.

I wonder whether this, too, is a mark of the times: where the performance of both the everyday and the spectacle involve a kind of ‘pillowing’ of the real world, as the only remaining method of validating one’s right to dream, to build things, to perform. Artists erect shelters for their ideas in order to present them, making their own context for work where none is to be found elsewhere. Improvised frameworks for ideas of ideas of ideas. Necessary abstractions. This is what I must have meant by “spectacularly provisional”.

What these performances have in common is a justifiable suspicion about the culture we live in, and a championing of the idiosyncratic qualities of shared experience, including its shared irony. Is irony the new form of criticality, synonymous with self-reflexivity? Call it cynicism or realism or pure fantasy, these events are better experienced than talked about. If just ‘being there’ describes the essence of what authenticity means in this realm, I am happy to witness it. Friends gather around, with laughter and sincerity.

More fun iPhone sketches by Walter Scott!

Dustin Brons

Luciana D’Anunciacao

Macarena Perich-Rosas

VestAndPage

By: Caitlin Chaisson Written On: September 29, 2013

LIVE Biennale @ VIVO Media Arts Centre, Wednesday September 18, 2013.

This article is published in collaboration with Decoy Magazine

On the sidewalk outside of VIVO on Wednesday night, a man was seated next to a table-sized block of ice. He looked rather cold for a balmy September evening and wore black cotton gloves, which he periodically removed in order to rest a bare hand atop the slab – doing so for extended lengths of time. When his circulation began to condense in purple pools, he would withdraw his frozen extremity, placing it back in a glove to warm it.

Congregating around Alain-Martin Richard’s Mediation of Natural Events was a mixed crowd of performers (betrayed by their crushed red velvet dresses and tuxedos) and patrons, passing time while waiting for the doors to open. Wednesday marked the beginning of six days of performances from international and Canadian artists for Vancouver’s eighth edition of LIVE Biennale. Alain-Martin Richard (Canada), Jürgen Fritz (Germany), Guadalupe Neves (Argentina) and Lori Blondeau (Canada) opened the festival with markedly different performances, yet each carried what I understood as an interest, to some degree, in obsessive staging. Despite beginning the evening with a meditation on the natural, the performances to follow were much more idiosyncratic, or engaged with artifice: Fritz’s repetitive rapture, Neves’ frantic digging around in the dirt, and Blondeau’s fixation with the plucking of rose petals.

The crushed velvet dresses and tuxedos belonged to the singers of the Vancouver Bach Choir, led by their conductor, and hired to co-perform with Fritz. Having just finished a performance art pre-festival workshop for the Biennale, and as co-founder of Black Market International (BMI), Fritz is an artist long familiar with collaborative practice. In its typical incarnations, collaboration frequently brings to mind the idea of ‘integration’, or a sort of fraternal partnership that involves sharing and compromising. For BMI, and Fritz in particular, collaboration is more a concern with presenting events simultaneously, in “parallel,” without forcing them to be conjunctive. This is a position I have reservations about, largely because I wonder whether collaboration is the right word. But regardless of whether it was the result of collaboration or coincidence, I was surprised to find that with this particular performance, where the artist had established a gap between the parallel acts, was in fact where I found the collaborative aspect of the work the most audible.

In a tight fist, Fritz grasped the yoke of a sizeable hand bell. He bore the instrument with his eyes closed and engaged in trance-like swaying that suggested he was not about to follow the conductor’s lead. The choir and the artist would be directing separate parts of the performance alongside one another. After several mute and motionless minutes, the choir took the conductor’s lead and began to quietly enter into song- Miserere by Henryk Górecki As I began to fall into my own relaxed state, lured by the conditioned voices, I noticed Fritz becoming even more engrossed. By the time the choir began to crescendo, Fritz’s swings had reached chest-height, and the bell began to clatter. It’s metallic sound cut sharply through the voices of the choir.

The first toll was startling. It certainly appeared to produce sound parallel to the choir’s, as opposed to one integrated, but Fritz’s genuine absorption in his movement made me hesitant to interpret the sound as obtrusive. Over and over, Fritz methodically rang out, and over and over the choir repeated the last few minutes of Górecki’s original score. The repetitive aspect, perhaps, in both the music and the tolling of the bell, seems to reflect an interest in the controlled and the conditioned musician, the audible body.

At one point during the performance, the choir stood silent while Fritz continued the bell’s cadence: raising his hand over his head in front of his eyes, then swinging it backwards to raise it over his head again. If it had been a collaboration in the typical sense, one would think of Fritz’s musical accompaniment as some sort of percussive addition- something keeping a beat. But it was quite clear that Fritz was not just maintaining rhythm in this performance, and this is where the collaborative gap, I believe, took its shape. The bell and the voice were not in harmony; the bell formed the shape of the voice, and the voice formed the shape of the bell. Parallel acts allowed for a collaboration of sound. Each performance significantly affected the other, changing the entire dynamic of the event as a whole. This was most palpable when the variables changed. At one point, the choir stopped singing; the bell sounded entirely different, though Fritz was doing the exact same motions as he had been doing before. It provided us with a moment where we could hear the influence one had had on the other.

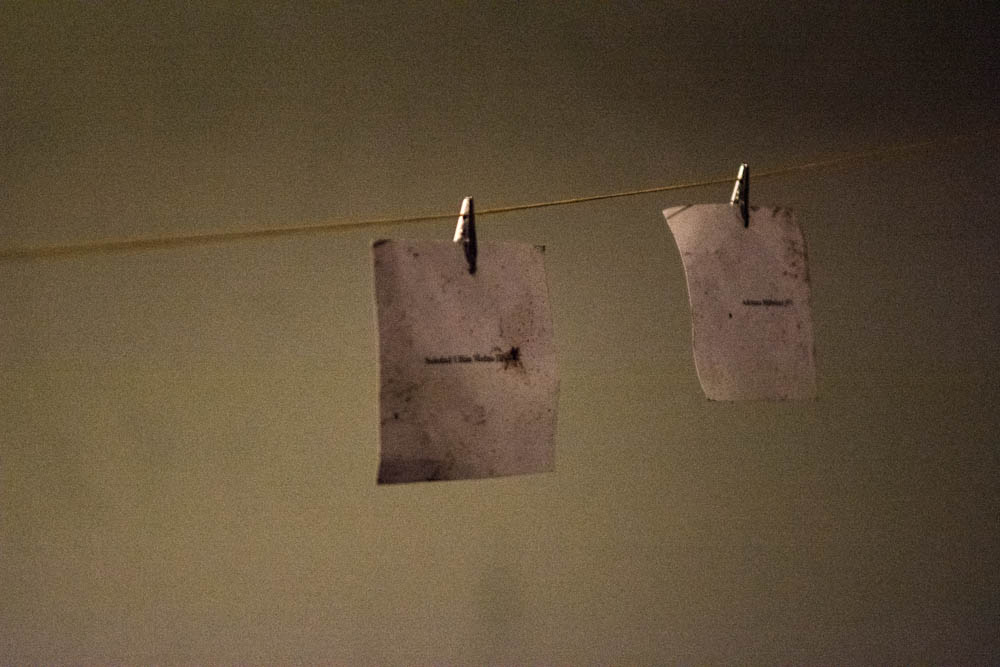

Whereas Fritz’s performance aimed to maintain a sharp distinction between parts of the work, Neves’ performance required an uninterrupted continuity. The phrase, “no guarantee” flashed on the wall as a projected text. Neves stood at the back of the room wearing a plain white apron, her black hair draped to conceal her face. Next to her was a silver basin with white flowers planted in soil. Crouching down to reach a handle, she began to drag the object across the floor, the basin too heavy to lift. One step at a time, she headed towards the opposite corner of the room. A spool of string, whose tail was nailed to the wall, looped onto the basin. Neves moved slowly away from the wall where she had started, but the nearly invisible thread continued to literally tie her to the spot where she began. Much of Neves’ performance took on this type of metaphorical quality. Each action was delicately crafted with purpose. When she finally reached the opposite wall, she unwound the extra string, knotting it around another nail to create a line that ran from one end of the room to the other.

She sat on her knees near the basin and began to pick the flowers. Shoving them quickly into her hair and the neck of her shirt, she fashioned a haphazard wreath for a collar. When all the flowers were plucked, without hesitating she quickly moved on to the dirt. Shovelling it out with her palms, debris sprayed all over her apron and the floor. She picked out a small white square note, and then another, and another, shoving each one into the pocket of her apron. When all the soil had spilled over the sides of the basin, Neves stood up and brushed the dirt from her lap. The notes Neves unearthed were read aloud by the audience and hung on the very line she created by dragging the basin. “Your portrait” or “His trousers,” “Our photos” or “Their documents” were in the company of names and numbers, such as “Lidia D’Avolvia (86).” These fragmented sentences, seemed to refer to equally fragmentary or incomplete memories.

Memory is often something appointed to the periphery of the mind, and not something we readily envision as corporeal. Neves’ performance offered a reminder that this is not the case. Memory is as much a manifestation of the body as it is of the mind. Thoughts and memories are planted in our minds, we carry them with us, we act upon them, we dig them up, and we make attempts to piece them back together with the help of others. Perhaps the crux of the performance, in my opinion, was the thread. Dragging memories along with you is one way to create a tie from where you once were to where you are now, and that bond is the very same fragile site along which you try to pin the remnants you find. By smartly using metaphor (which is also relegated largely to the domain of the mind) as the literal platform for her performance, we are invited to remember that actions can embolden our thoughts.

Heavy and cumbersome, as Neves’ laboured movements demonstrated, memories can be weighty and indulgent – and easily exaggerated in the presence of love. Blondeau’s performance was introduced by a suggestion that this was a more casual piece than the previous acts that evening, welcoming the audience to wander in and out of the room while the performance was in process. Blondeau stood before a wall she had been working on, absorbed in her task. She took no notice of the audience, who seated themselves- too cautious to initially heed the invitation to mill about. Blondeau had formed two human figures out of rose petals and she was working on the third, plucking petal after petal and methodically sticking them to the wall. Blondeau was making it clear that the act of piecing together these life-sized flowery silhouettes was a considerable undertaking. After finishing the third figure, Blondeau headed to the back room and re-emerged with a bottle of wine. She cracked it open, and poured herself a glass. I could sense the audience waiting for the next part of the performance, feeling like this event would mark a shifting point, but instead, Blondeau merely dragged the fourth bucket of cut roses beside her, sat on the floor, and continued working on the next figure. With her iPod on a shuffle of Coldplay, Van Morrison and Lauryn Hill (a soundtrack eligible for the heartbroken), her glass of wine beside her, and her rose petal figures, the tableau seemed fitting for a romantic comedy. As an artist whose work deals frequently with the development of personas and alter egos, I wondered who this silent, introspective and busily occupied character could be. A crazed jilted lover, psychopathically recreating the figure of their lost love? A woman on the borderline between the obsessive and the histrionic? Yet, Blondeau never provided us with even the most remote suggestion that there was ever any emotion involved in the performance whatsoever. She hardly even looked at us.

Eventually, when the audience decided they had the gist of the performance plot covered, they began to chat among themselves, headed to the bar, or found new seats, while Blondeau took no notice. Some started to take bets as to how long it would take her to finish with the last figure, and it was only the audience’s gambling that made for the comedy part of this romance. Compared to Neves’, whose performance also involved an element of ‘crazed,’ Blondeau lacked the thoughtful depth in her performance that could have made her work even the slightest bit more compelling. As it was performed, her actions were superficial and vague, not exaggerated enough to successfully pull off the parody she seemed to be making.

Despite being presented with similar methodological approaches, the diversity of performances on Wednesday made for a curious evening. For the audience, there was no shock offered by any of the artists, but a gradual development of subtly shifting progressions. Perhaps the idea of staging is overly obvious when discussing performance art, but Fritz, Neves and Blondeau each managed to produce a conversation about very distinct experiences, through the careful development of tight theatrical parameters- Fritz never straying from his mechanical swings. That being said, it was clear to me from the shallowness of Blondeau’s work that these parameters need to be formed in conjunction with something else, not used as the presentation itself. The stage can’t elicit as much as the performer.

–

All images provided by Ash Tanasiychuk, VANDOCUMENT.

Dark.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

Puppets and pantyhose. Blood, balloons, and broken glass.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta