Gary Varro

Documentation by Ash Tanasiychuk for VANDOCUMENT

Copyright © 2012. All Rights Reserved.

Documentation by Ash Tanasiychuk for VANDOCUMENT

Lori Blondeau, drawing with roses.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

A glimpse of Snežana Golubović’s durational performance.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

Guadulupe Neves performance, Sept 18 at LIVE 2013, to the disappeared of Argentina.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

I arrived at the courtyard of the Firehall Arts Centre around 11:20 Saturday morning. The four-hour durational performance by Margaret Dragu, Grace Salez, Judith Price and Sinéad O’Donnell had begun at 11 and was already in full swing.

The performance of these four women was quite different from those of Pancho Lopez or Christian Messier, which had taken place earlier in the festival program. The performances of both Lopez and Messier led their audience toward a single climactic moment, a surprise that revealed the logic and beauty of their action. Lopez smashed the vase full of Coca-Cola with his baseball bat; Messier opened his mouth and from it billowed a cloud of white dust.

The whole arc of their respective performances had led to that one moment. The actualization of these poetic images completed their pieces. Once revealed, any further performance was pointless.

The actions of the four women were of a different order. There was no arc towards climax. Composed of hundreds of actions and images, their performance continued throughout the afternoon. They worked through a few simple actions, which were repeated constantly, always with a slight variation, with a few new events occurring throughout the day.

Four hours is a long time to create a performance with a coherent conceptual framework. For this slow organic process of creation to succeed in engaging the public, the performers must work with an intense focus. Their individual acts throughout the period must have a poetic resonance, they must be coherent within a concept, and they must show some development. It’s a very difficult act to pull off.

Their show was called “Chaos”. Though the women worked in disparate realms, interacting only rarely, the over all feeling of the piece was, for me, not one of the world out-of-order. There was no violence, no anxiety or terror that I associate with a world gone amok. On the contrary I felt that these women were working to create some kind of order from a primeval and formless state.

Throughout the day Grace Salez remained blindfolded. She alternatively pushed and pulled a wheelbarrow full of rotten apples, walking a few halting steps from one side the courtyard to the other. Judith Price lay on a picnic table and struggled to climb out from a felt bag. Sinéad O’Donnell with a painted face, her dress stained red and covered with Vaseline and flour, walked dazed around the central tree placing small black ravens here and there. A whole dead fish lay on a bed of ice. Margaret Dragu sat ensconced on the deck over looking the courtyard. On a small table she had set-up her mending station with a tin of buttons, her sewing supplies, a few articles of clothing that needed care.

Each of the women created a unique space with a separate gravity and logic, which she developed throughout the day with a hundred slight variations. Turning your head from one performer to another, the eye was constantly caught anew by striking images: Judith cutting her toenails and covering her bare feet with band aids, Dragu singing karaoke version of “The Days of Wine and Roses” with her clients, O’Donnell, her hand stuffed into a loaf of bread biting off chunks and eating, and Grace always moving gingerly, her hands searching the space before her seeking something solid.

It is unfortunate that so few members of the Live audience came by to see this performance. It was a solid cascade of poetic images that rained down without cease. In one short afternoon, a lucky few witnessed absurd, tragic, motherly forces wrest form from nothingness.

Fortner Anderson

At the end of the evening, one of Anna Syczewska’s high-heeled shoes, the ones with the 10-inch spikes welded to their soles, remained impaled in the wall. The other lay at the base of the wall where it fell, under the gouged drywall. Her electric wheelchair stood empty, its wheels covered in crushed tomato, the result of its passage over the pile of rotten tomatoes. The tech team had put away the arc-welding equipment and the homemade gynecological stirrups that had held her feet as the professional welded the spikes to the soles of her shoes.

Nothing much clears a room quite as effectively as a 45-minute session of electric arc welding in an enclosed space. The blinding light, the noxious fumes, and the bludgeoning soundtrack pushed the majority of the audience back into the bar or onto the street for some fresh air. Syczewska in her sunglasses sat impassively in her wheelchair tippling from a wine bottle waiting for the slow industrial process to finish.

By the time the spikes on both shoes had been welded in place, it was evident that she had trouble moving her legs. They had remained splayed apart, held in place in her stirrups which would have looked right at home in a clinic run by motor-heads. It was constructed out of three lengths of welded chain, which formed the “Y” and a couple of pieces of bent re-bar that held her feet.

Once the welder completed his painstaking work, the crowd re-entered the gallery space and the show entered another phase. Syczewska stood upright momentarily with the modified shoes. As she balanced precariously, she rubbed a tomato over her legs. Unable to maintain the pose, she collapsed back into the motorized chair.

She maneuvered her chair back away from the audience. Motioning with her hands, she indicated to us that she wanted a path cleared in the rows of chairs. As a way parted in front of her, she revved the chair and moving forward at speed she hit the wall. One shoe remains impaled to this day.

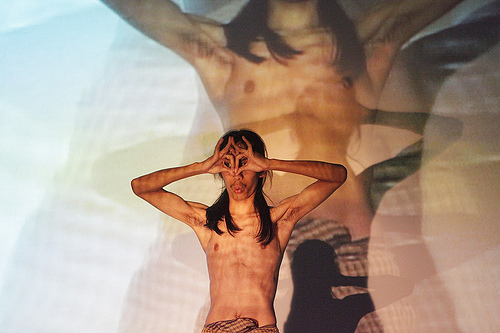

Moe Satt from Yangor Myanmar, presented a simple understated piece. His set consisted of a chair set before a screen. A camera captured both he and the set, and it its image on the screen behind Satt. The positioning of the camera and the video projector were such that it created an infinite repetition of images of Satt on screen, similar to the infinite series of images created by two facing mirrors. In this video version however, the images grew rather than decreasing in size and only the first couple of iterations were visible.

Satt began the show by removing his jacket and shirt. Bare-chested he adjusted the wrap covering his legs, taking care to tie it, in what I imagined to be the traditional manner. Having tied it at the waist he then gathered it up and tied it again to that it covered his genitals and buttocks leaving his legs bare.

He continued by making a number of stylized and symmetric gestures with his hands, positioning them over his eyes, on his face, or over his head. In the audience, we saw these in flesh and blood, as a black shadow projected on to the screen and in the cascading series of video images projected on the screen behind him.

Walking up to the audience he indicated that certain members should mimic him. Satt accompanied these gestures with a whistling of single tones.

At a certain moment, Satt closed the action by walking to the back of the stage, kneeling and bowing.

In analysis Freud spoke of the screen memory. This was a memory, which served to protect the ego from the effects of trauma. It accomplished this by covering the memory of the original trauma with the memory of something else, usually another anodyne event. During analysis the analysand, would return to this harmless memory and to a certain extent this screen memory would come to stand in for original difficult and painful memory.

Anne-Sophie Turion piece recounted a series of childhood memories; a car drive around a lake with the family, a the fragment of a conversation on a telephone, the music her father played on their car drives, the banal exchanges at the family supper table.

The piece began at dinner table set for a party of seven. On the wall behind the set, the Turion’s text and simple stage directions were projected onto the wall. In her halting English, Turion began by telling us that she wished to share a memory with us, but that it was difficult to find the precise memory.

This opened the way to her fragmentary, repetitive and partial description of a number of childhood memories. Interspersed with her narrative she presented the lush musical excerpts that her father enjoyed listening to in some distant past. These included the theme music from the film Jurassic Park, David Bowie, the Doors, and the Hall of the Mountain King.

We never learn of the hidden trauma, or indeed if there were such a thing. There are repeated mentions of her brother and mother but everything is banal to an extreme.

The piece climaxes with Turion climbing up onto the dinner table to lip-sing a song, one of her father’s greatest hits.

It ends as it began with the table reset for seven and Turion repeating her introductory phrases.

We are caught in a neurotic return; never capable of escape from the terrible gravities of a childhood we can never fully recognize and never escape.

Fortner Anderson