Guillaume Désagnes and Frédéric Cherbœuf

Documentation by Ash Tasnasiychuk for VANDOCUMENT

Copyright © 2012. All Rights Reserved.

Documentation by Ash Tasnasiychuk for VANDOCUMENT

Documentation by Ash Tanasiychuk for VANDOCUMENT

Documentation by Ash Tanasiychuk for VANDOCUMENT

By: Karol Sienkiewicz

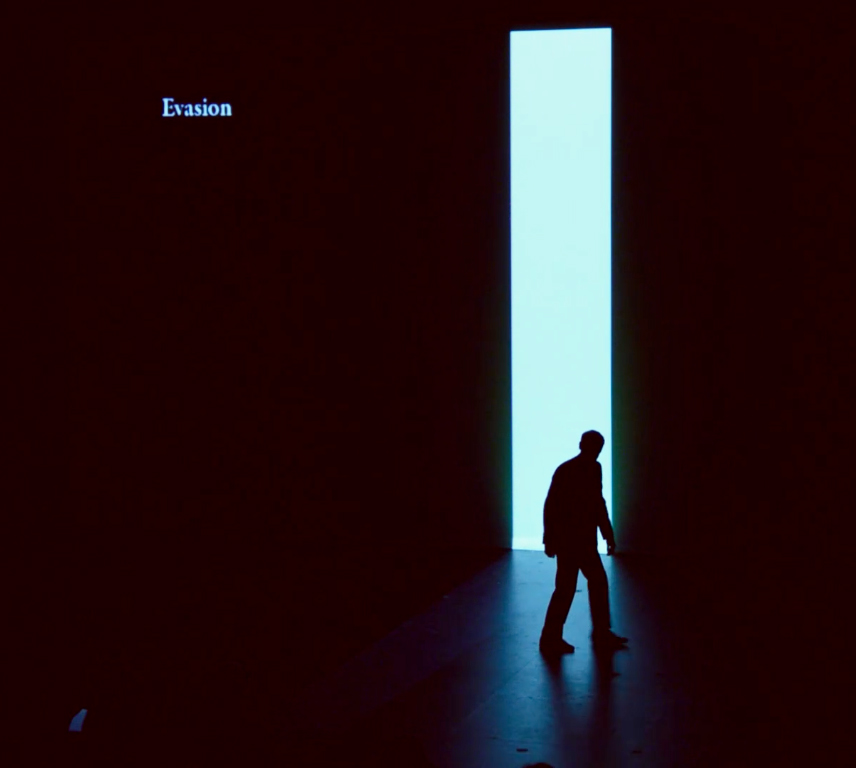

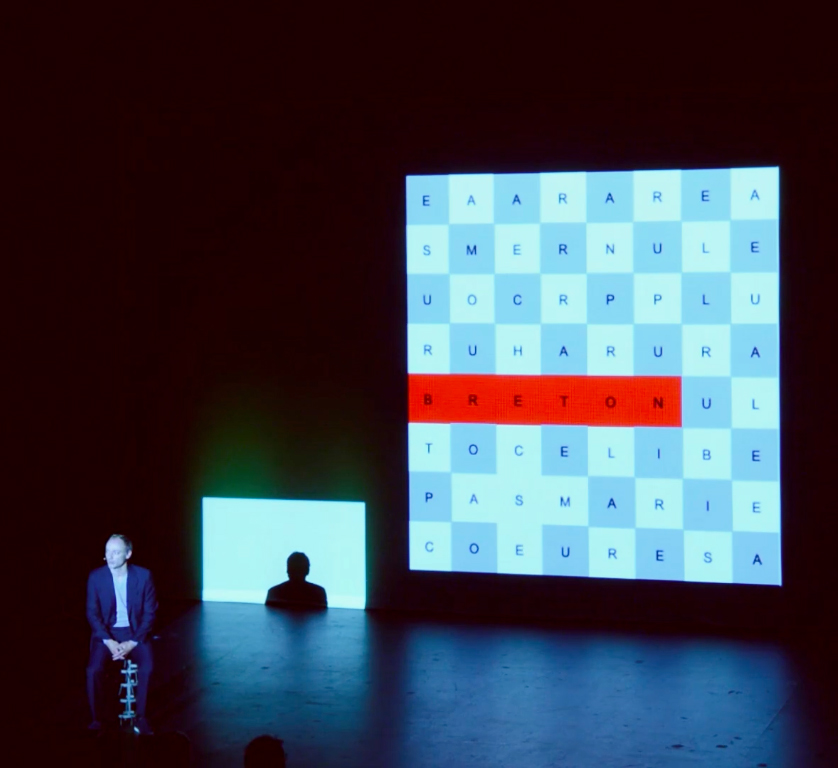

LIVE Biennale @ VIVO Media Arts Centre, Friday September 20, 2013.

(This article published in collaboration with Decoy Magazine)

The Vancouver LIVE Biennale’s third day of programming demonstrated the bare bones of what a performance festival usually means. Some wiggling and squirming, a pinch of audience interaction, and some old-fashioned, yet widely tolerable body art. No ingredients missing from the recipe, all courses palatable—but very few surprises. Friday night at VIVO was at times dynamic, at times an abyss of tediousness: Spielberg’s “Jaws” followed by Warhol’s “Empire”.

Five performances in three hours, two beers, no cigarettes. In the background, Gary Varro presented a durational performance in On Main Gallery, which was visible from the space’s street windows. Fellow imbibers gave him a perfunctory glance during breaks. In a nutshell, it was a huge, golden, shiny worm. It was visually attractive, and quite gruelling for the performer, I presume. The first two performances, presented by locals Lauren Marsden and John Boehme, managed to enliven the audience, who responded eagerly. The third one by Singapore’s Jason Lim, featuring candles, a tree branch, a stone, and feathers, made them sleepy. This was the calm before the storm: the grand finale by Polish duo Suka Off. But did they meet the expectations of a headlining act?

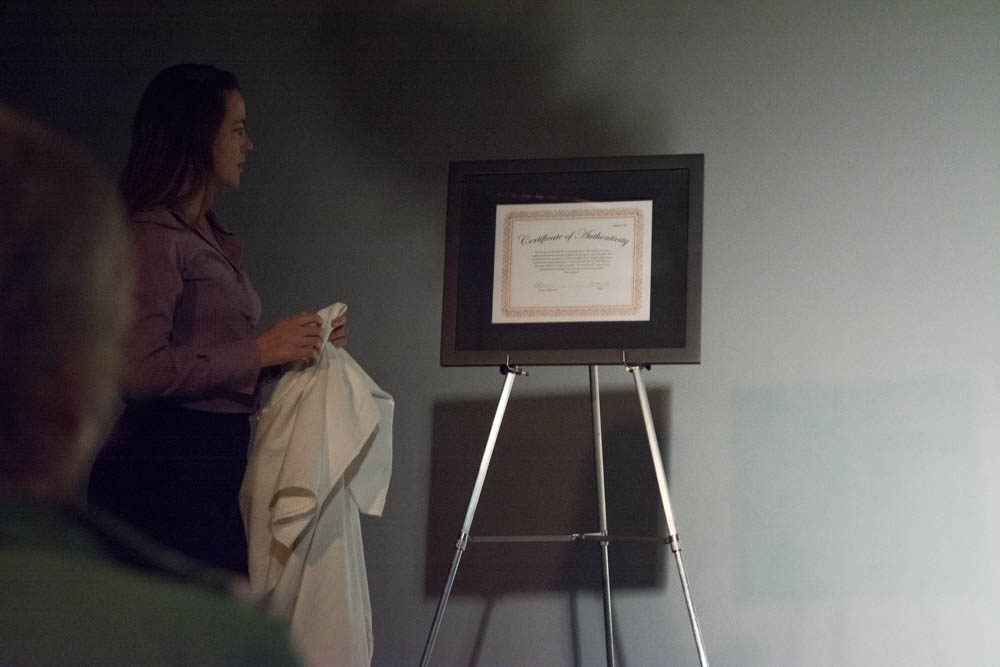

Let’s not get ahead of ourselves. First off, the performances of both Lauren Marsden and John Boehme investigated the very nature of performing in front of a live audience. Marsden presented a delegated performance that was an auction of the performance of the auction itself, conducted by Crystal Campbell, a professional auctioneer. It was the second performance in a series, or “edition”, of only three. And what was sold was not the performance itself, but a keepsake, a neatly framed certificate. Was Marsden trying to question the art market? If so, then she failed in the same way conceptual artists failed to produce unmarketable works half a century ago. Marsden also failed when it came to money. If I recall correctly, the estimated worth of her performance was valued at more than two grand; after half an hour of bidding, her work fetched the price of 218 dollars.

The rules the art market imposed on the performance by Marsden became a limitation. Presumably mindful of these many traps from the word go, Marsden and the auctioneer succeeded somewhere else. For me, the interest was not so much in the idea of literally auctioning off the auction, but in conducting an auction about the auction and the auctioneer. It reminded me of Jérôme Bel’s spectacles, in which a dancer talks and dances about their own dancing career. Similarly, Campbell interrupted bouts of rapid-fire bidding with poignant stories about her professional life and experience. As she switched roles from stand-up comedian to lecturer, from entertainer to auctioneer, it became apparent that in order to sell, Campbell needed to control the audience’s emotions, which she did perfectly well. However, some of her stories lacked punch lines. If, like in Bel’s case, this was a play, these small imperfections would be refined with time and the performance would really get into the groove.

Before the applause abated, another performer took the stage and continued to clap his hands. Disguised as a minor-league baseball manager, John Boehme turned the action that is supposed to follow at the end of an act into the performance itself. Clapping his hands in every possible way, Boehme managed to keep the audience in high spirits for quite a long time. They sometimes joined him in clapping, even egging him on with shouts of encouragement. Later, they simply observed him as he became more and more fatigued. It was an exercise in exhaustion. When he finally stopped, a volley of real applause thundered.

But what promised to be an interesting evening was later bogged down in a jejune performative rut. Jason Lim’s props belonged to a classic repertoire of performance festivals. His slow-motion act, beginning with the artist being pinned down by a rock and ending with the drop of a feather, was the quintessence of lofty spirituality. And a doctor could have prescribed it instead of sleeping pills. You know, it takes a lot of time for a candle to burn out. While some of the audience made their way to the bar, others were mesmerised by Lim as he motionlessly balanced a huge branch on his head. I felt stuck between a reviewer’s call of duty and my internal instinct to escape. Meanwhile—click, click, click—the photographer fired his shutter, as if he wasn’t just sitting in the front row of an art show, but also on the front line of combat. But, bent over and focused on his work, the photographer revealed his cleavage to the back seats. Finally, some food for thought. I’m saved. TGIF.

While Lee was struggling with his stones, candles, feathers and a branch, I couldn’t wait for the next act. Suka Off, billed as one-of-a-kind, were to blast off the evening’s fireworks. ‘Suka’ in Polish means ‘bitch’. But sometimes the higher the expectation, the bigger the disappointment. A man in white and a woman, who emerged naked from a black costume harnessed inside a meshed metal cage: together they jumped through hoops to maintain tension throughout their performance. Their bag of tricks included strobe lights, fluorescent paints, and baleful sounds. It all boiled down to the switch of gender roles. The woman emerged from the submissive black into the active white (she put on the guy’s white clothes at the end of the piece), while the guy shed his white attire and retreated into passivity (he ended up inside the black costume). That was all? “Jesus. Fuck,” as Bridget Jones once famously said. It was as if a skin-flick actor lost his vigour before climax. There was no climax at all.

Though the evening began with critical insight into live performance, it descended into the all-too-well-known routine. TGIF, I thought again.

–

All images provided by Ash Tanasiychuk, VANDOCUMENT.

Full disclosure: This article was co-edited by Stacey Ho, a staff member of LIVE Biennale and Lauren Marsden, editor of Decoy Magazine and participating artist. No significant changes to the author’s original text and opinions have been made.

Dustin Brons’s Nauman-inspried potato chip piece.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

Lori Blondeau, drawing with roses.

Videographer: Sebnem Ozpeta

re-LIVE Vancouver was a tableau of tribute artworks at VIVO Media Arts Centre on September 25 2011. Installed like a gallery, it became an art exhibition with live art works that were scraping, rubbing, running around, wiggling and jiggling in the corners and along the walls.

Sponsored by the City of Vancouver’s 125th Anniversary Grant Program, it was a reiteration and redistribution of performative creations by some of this city’s most iconic artists. In alphabetical order:

Warren Arcan, Kate Craig, Margaret Dragu, Rodney Graham, Glenn Lewis, Vicent Trasov, and U-J3RK5 (Ian Wallace, Jeff Wall, Rodney Graham –again, Kitty Byrne, Colin Griffiths, Danice McLeod, Frank Ramirez, David Wisdom).

Glenn Lewis and Margaret Dragu were in audience. (Maybe others from that list too, but I wouldn’t have known them.) Kate Craig passed away in 2002, so I am quite sure that she wasn’t there, though a number of women were kind of dressed like her.

How do we do tributes? Why do we re-iterate, repeat, re-imagine, remark, re-play, re-use, repeat, appropriate, re-make, re-stage… ? If we remark on something do we assign it new meaning? If we copy the motions –practice them with our limbs, do we become the past for a moment, or do we ingest them and then finally change their meanings? Who authors the past, when it gets repeated? Derrida said that the original use should not be prioritized over the secondary. In the late 60s Foucault predicted that by now we would be over the author-thing.

Curtis Grahauer’s empty stage was funny. Even though it was a karaoke invitation – the mikes, the music and the words were all in place for us to play and sing along—no one dared to touch the setup, which was meant to exactly mimic the placement of the 8 band members as they were posed on their album cover. The absent rock band. Is anyone counting, how many local tributes have been turned down by the most famed of that crew? (OK forget about them. No one wants to sing along with them anyway.)

Ron Tran’s Peanut, Leopard, Sharks miniaturized the most familiar of performance art props from Vancouver’s early performance art days and put them into the hands and onto the bodies of a pack of preschoolers who were let loose in the gallery for the first couple of hours of the evening. Yes, performance art was a preschooler in Vancouver when these characters were first running and swimming around in circles. The original artists had ridiculous aspirations of taking over the city and the world. (I can imagine them falling down from laughing so hard, just like those kids.) In some ways, Vancouver art has lived up to their impossible international ambitions, of which this show is a reminder. But the reiteration of these works on the bodies of really tiny kids also puts those antics into a kind of disappointing contrast with all of the really smart and serious, institutionally bound, art that gets internationally distributed these days. Only preschoolers have fun now?

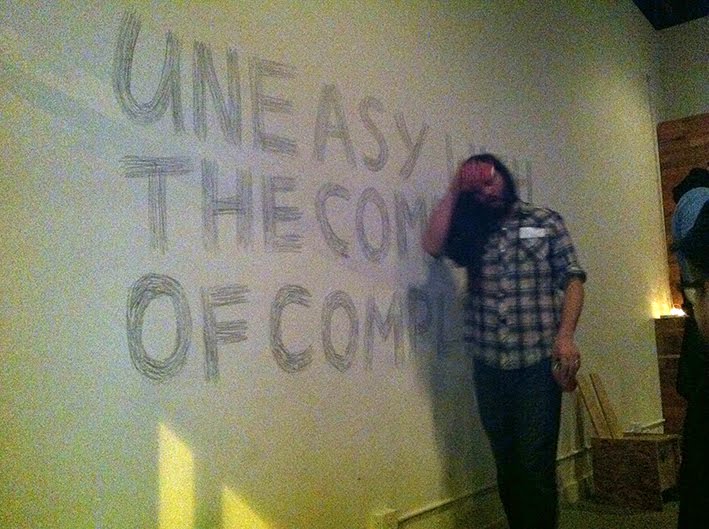

Both Raymond Boisjoly and Francisco-Fernado Granados produced performances by themselves, in front of us, and in response to more senior artists who had also performed at this year’s LIVE. Boisjoy made a simple drawing that spoke back to the overall work of Warren Arcan who had performed Why I am So Beautiful a week earlier in the same venue (VIVO Media Arts Centre). Boisjoly and I talked about Arcan’s particular interest in using worn and familiar materials to work out fantastically intense psychological meanings. In Why I am So Beautiful Arcan used every objects from his mysterious box to speak variations of that beautifully twisted scenario of the love affair. It is complicated, the love affair. The third or the forth or the fifth love affair. First with a stone, then a stuffed bear… then on the phone. Complex, yet comfortable in its familiarity, and increasingly uneasy.

That is only one reading of Boisjoly’s simple gesture of using a beer can to scratch the text,

UNEASY WITH

THE COMFORT

OF COMPLEXITY

onto the gallery wall while everyone partied.

When I read it after he had finished, I was thinking that if the artist knew how many times I uttered the words “its complicated” to newcomers to Canada who didn’t understand things like the government’s abysmal record of unfair dealings with Aboriginal Peoples, he would be uneasy. What do those uneasy words mean?: I can’t take the time to explain that issue to you…or I don’t know the answer but I can’t admit that I don’t know…or I cannot speak….?

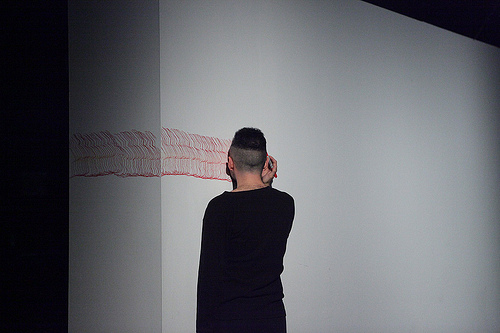

Francisco-Fernado Granados’ work was a direct appropriation of a previously performed work by Margaret Dragu. Like a piece of sampled music, he took the smallest of elements from her Western Front performance that is briefly captured here (http://www.livebiennale.ca/1999-2001.html – watch for the tiny clip of Dragu leaving a kiss mark) and repeated it until the surface that he worked against ran out. This work solidified the way that live art was inserted into the gallery form, seemingly a curatorial intention of the re-LIVE Vancouver event. Granados himself has been inserting his intense physical gestures into gallery settings as a way of marking the space with his slowly moving body. His body has been leaving its mark on these revered spaces with materials that belong more on the surface of paper rather than on the body: a red marker in this work, untitled (spatial profiling), or gold gilt (gold in his work is a recurring mark for mourning –of gold mine victims in Guatemala and of a lost lover) as in the recentCrown performance and installation at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre in Vancouver. Margaret Dragu’s participation in Chaos a day earlier for LIVE in the courtyard behind the Firehall Arts Centre was much less about imprinting the body on a cultural or exhibition space, than about working through an evolving series of gestures and materials in a socially evolving context. During Chaos, the audience came and went as four women performers, Sinead O’Donnell, Judith Price, Grace Salez and Margaret Dragu, invented relations with each other, the space and the materials that they had gathered. This was one of those largely generous events during which the audience could ingest a repertoire of actions and reactions that held uncanny fascination and imaginative potential. From a long practice of making those generous Aktions available for her audiences, Dragu’s single kiss mark on the white wall (1999?) was the action that Granados chose to reiterate and practice until he was stained and probably a little sore.

Thank you LIVE 2011 for marking up the city again with new and renewed actions, gestures, forms, poems, songs, texts, uncanny relations…. in such a large and generous display.

Lois Klassen

Well folks, last night was the first night for Live 2011! An auspicious start to what should prove to be a powerful and fun-filled festival.

Well folks, last night was the first night for Live 2011! An auspicious start to what should prove to be a powerful and fun-filled festival.

Fortner Anderson kicked things off, reciting the long poem, “Drifting into Fire”. The piece is one of three from a cycle called “Annunciations”, which each stem from investigative reports of modern disasters. Drawing from NASA’s accident report on the Space Shuttle Columbia, Anderson’s dynamic delivery shifted rapidly between ecstatic and mechanistic. At the most intense points of Anderson’s performance, it felt as if words were being forced from his mouth, like they could barely squeeze themselves out. Fitting, given that his subject is catastrophe at a scale that is at the very limits of what we can express or fathom. By truly considering the details outlined in these reports, Anderson saves these contemporary events from dry factuality. Our collective experience of tragedy takes on the feeling and gravity of something closer to Blake instead of the numbness of a newsfeed.

Following was Dana Claxton performing The Elsewhere with the help of Sam Bell. Central to this piece was a vessel made of hide, brightly painted with a long fringe at the bottom. Sam, who has collaborated with Claxton on several films, mentioned later that Claxton has a collection of such special objects. Despite the predominant position given to this beautiful container, it remained untouched for the majority of the performance. Instead a delicately balanced space was slowly built around the object, using stones, gestures and sound.

The piece proceeded in a gratifying 4/4 time, with Claxton moving backwards, eyes shielded from sight. Four bags of large grey stones were emptied on the floor. Four pairs of stones were each struck four times and laid out to make four paths radiating from the centre of the space. Four new bags of rocks were each dropped four times, the gesture creating a forceful and heavy sound, then emptied on the floor. Polished stones were revealed in red, black, pale yellow and white.

When Claxton finally approached the container, she began for the first time to move forward, circling the room and shaking the vessel so its contents rattled. A final action, the container’s contents were poured out in the centre of the room, revealing rainbow-hued abalone shells and handfuls of turquoise. Surprise at the sudden unveiling of this colourful bounty. A song is played on the stereo, traditional, aboriginal, female, and the audience is invited to take with them a “token of mother earth”. We are left with a gift of beauty.

This place, this Elsewhere that Claxton created last night, conveyed a specific conception of space, an ‘Indianized’ space. The materials and structure of her piece invoke a space that is organic, natural, harmonious. By offering us the materials of her piece, she implies a space that can shift and travel, as well as a space of sharing.

Claxton’s performance was nicely balanced by the cheeky humour of Jean Dupuy, who presented three pieces in sound and video. In B. versus B., a ‘stuttering’ author plays Beethoven’s Sonata #9 and Brahms’ Sonata #3 out of two separate speakers as images of the venerable composers slowly revolve on two back-to-back laptops placed on the floor. Not only were the two poor B.’s pitted against each other, but they also had to face the trial of presentation through digital technology. Some (unintentional?) audio glitches added to the stutter of the piece. Brahms’ gaze remained sulkily fixed on the mouse cursor that graced the laptop screen.

Next, a performance with the lighthearted spirit of Chaplin, preserved on 16mm film. Shot in 1976 from a bird’s-eye view, Dupuy and his wife stride towards each other in the middle of the street. They meet in the centre of an intersection and embrace. The camera zooms as they strip and exchange clothes. She has big, light yellow undies; I think his drawers are black. They fumble around a bit, dress, and as a final touch, exchange eyeglasses. Arms around each other’s waist, they walk merrily down the street. The couple turn a corner, and are gone. Simple and charming.

The final piece was a sound work of the train from Paris to Bordeaux, at the time the fastest train in France. Recorded using the train’s toilet bowl to amplify the sound, the Western Front’s audience was treated to fifteen minutes of this hours long piece. Dupuy recommended that the audience lie on the floor to enjoy the vibrations from the sound waves. Some dutifully complied though others were put off by a warning that the sound would be very loud. Despite this notice, when I laid down I found the irregular yet repetitive overtones of the moving train acted as a sedative to my prone mind and body. As I enjoyed the calming effect of these mild tremors across my back and legs, I distinctly felt the footsteps of people quietly exiting the room, bringing to a close the first night of the Biennale.

– stacey