October. 15th, 2023

Russian Hall

2:00pm

The foundations for “Little children our beings they found you” – mijua’ji’jk ntininaq weji’skesnik arose from a workshop Michelle Sylliboy (L’nu/Mi’kmaq) led during the Antigonite Art After Dark Festival in 2021, directly responding to the recent uncovering of the remains of 215 children at the Kamloops Indian Residential School site. Debuted at Nocturne Halifax in 2022, this work engages light, translation and community reflection through interactive installation and performance. Utilizing light-box projections and messages written in komqwejwi’kasikl, the L’nuk hieroglyphic written language, Sylliboy asks participants to contemplate their own layered connections to the histories embedded in this land.

Description

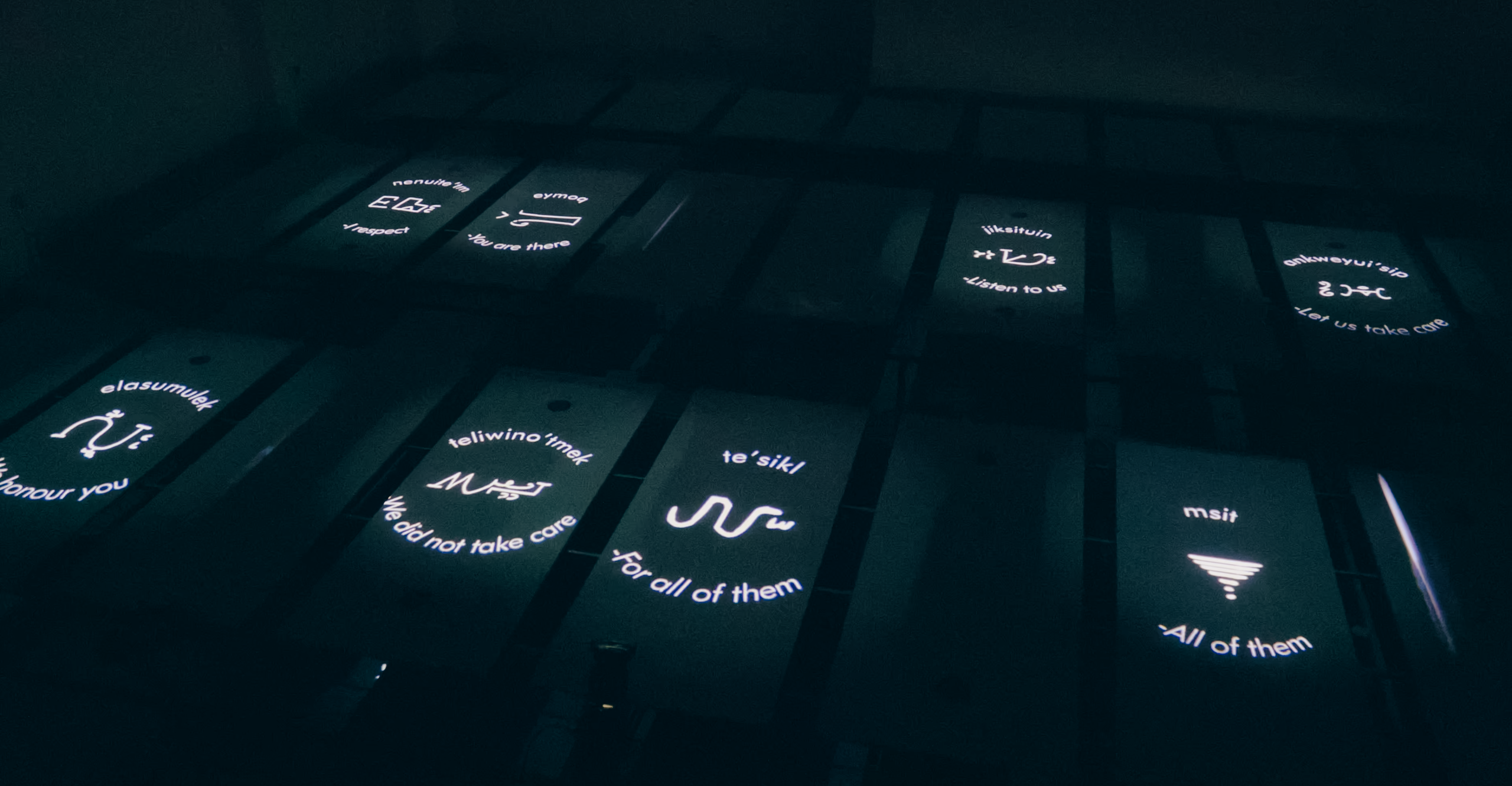

Upon entering the darkened hall where “Little children our beings they found you” – mijua’ji’jk ntininaq weji’skesnik took place, viewers were met with a series of triangular light-boxes arranged around the centre of the room. As folks approached these structures, sensors activated projecting a light message onto the high ceiling in three languages: Komqwejwi’kasikl, the Latinized L’nuk language, and English. These messages, which were gathered from community members during earlier stages of the project, intermittently lit up as people moved through the space throughout the performance.

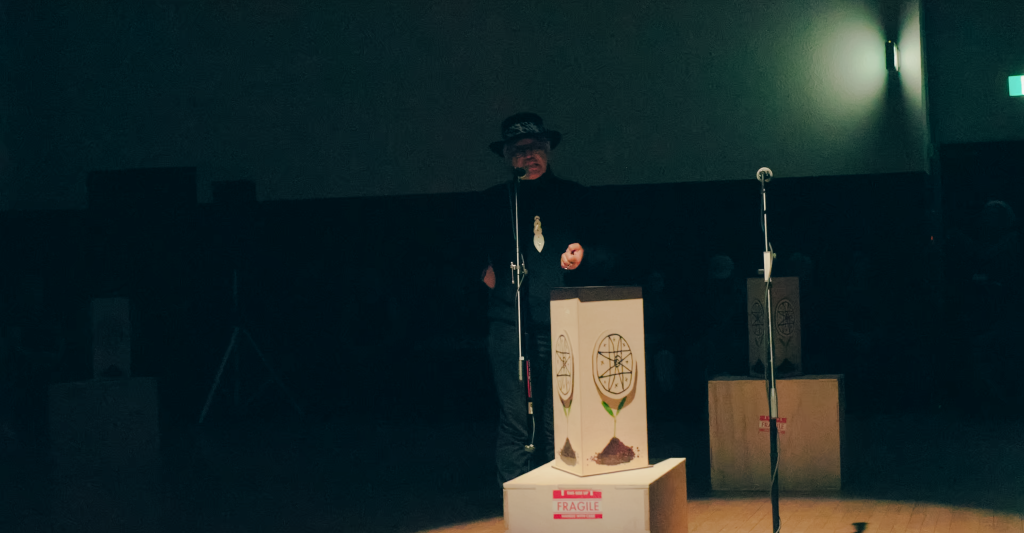

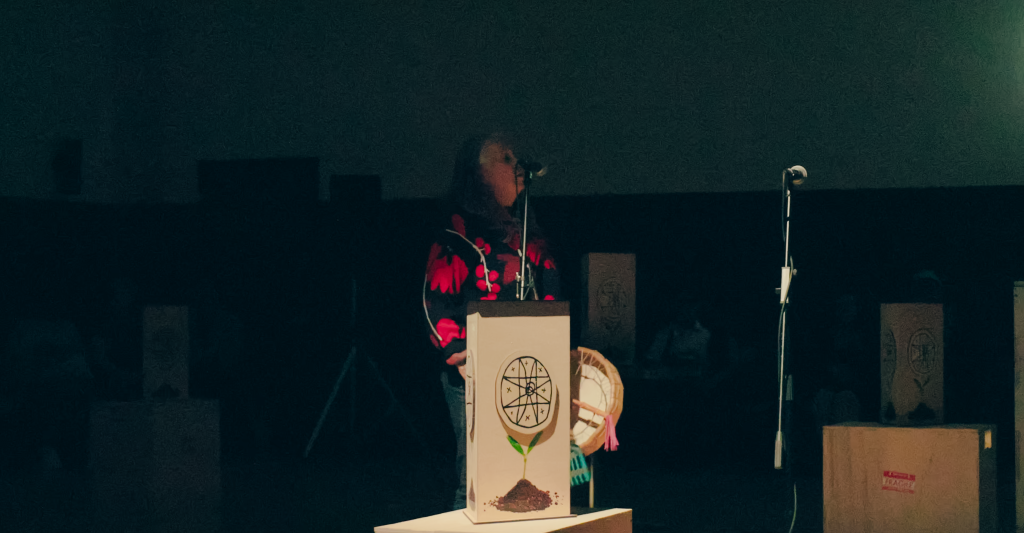

T’uy’t’tanat–Cease Wyss (Skwxwu7mesh, Sto:lo, Hawaiian, Swiss) opened the work with a song sung when First Nations leaders traveled to England to meet with the Monarchy and assert their ongoing presence on, and protection for, their lands. Following this offering, Sylliboy spoke about her work, explaining a bit of its backstory and layered resonance. After this the group M’Girl, led by Renae Morriseau (Cree, Saulteaux), shared numerous songs which spoke about the emotional impacts of the residential schools, including a lullaby by the late Nlaka’pamux elder Shirley James. As the performance progressed, folks continued to move through the space and interact with the light-boxes. Vancouver Opera cellist Heather Hays created a contemplative ambiance, and at one point Loretta Williams (Tswwassen Nation) spontaneously offered her respect for the important work Sylliboy is doing. The performance closed with a song which Morriseau’s brother received during a sweat; a healing song to “honour all life,” from plants to four legged creatures to humans.

After the performance, the audience was invited to choose a phrase from the Komqwejwi’kasikl glossary, write it out and place their messages onto the map of residential school sites across Canada. Leaving their thoughts for the children as messages which would become part of future iterations of the work.

Performers

Heather Hays (Cello), Michelle Sylliboy (Concept, Facilitation), T’uy’t’tanat Cease Wyss (Welcome/Singer)

M’Girl Singers: Deanna Gestrin (St’at’imc), Cheri Maracle (Haudenosaunee, Irish), Renae Morriseau (Cree, Saulteaux) and Michelle Bardach (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw, We Wai Kai Nation)

Review of Michelle Sylliboy’s “Little children our

beings they found you” – mijua’ji’jk ntininaq

weji’skesnik

by SF Ho

December 2023

Michelle Sylliboy is finding new ways to teach the L’nuk language of her people. Before entering her installation “Little children our beings they found you” – mijua’ji’jk ntininaq weji’skesnik, participants are asked to write a message in this language to the children who were murdered while attending residential schools—the government-sponsored religious schools established to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture. I look through the Komqwejwi’kasikl glossary provided in a black binder and squint at unfamiliar squiggles that move across the page like living creatures. The shapes remind me of hearts, waves, and tiny architectures. I choose a phrase about love and place my post-it note message on a map of Canada marked with residential school sites.

Sylliboy remembers encountering her people’s written language as scrolls of the Lord’s Prayer hung up in the homes of family members and neighbours. Even as a young person she was curious as to what these characters were and why she couldn’t read them. This was the beginning of a life long project of reviving Komqwejwi’kasikl, the “suckerfish writing” of the L’nuk people. Sylliboy describes her language as a verb based, descriptive language that registers how no two people see the same thing in the same way. Her work with the language is inspired and guided by her late elder Murdena Marshall, who was a beloved knowledge keeper whose accomplishments included a co-authored publication on the history of the L’nuk language.

The history of Komqwejwi’kasikl includes colonial encounters that attempt to revise and posses this precious part of L’nuk culture. Missionaries “discovered” Komqwejwi’kasikl in the 17th century when a priest witnessed children writing the script on birch bark and subsequently used it to spread the word of God. Prayers and hymns in the Komqwejwi’kasikl writings were reproduced and are still preserved in Vienna, but this valuable record has never been easily accessible to the L’nuk. In contrast to this hierarchical hoarding of knowledge, Michelle envisions a collaborative and community based way of teaching and sharing Komqwejwi’kasikl that engages not just the mind, but all of the senses. So far her project has encompassed a book of poetry, a whalebone art installation, photographs, animations, and public art works, as well as the installation that I am encountering today and a future project made from the map that I have contributed to.

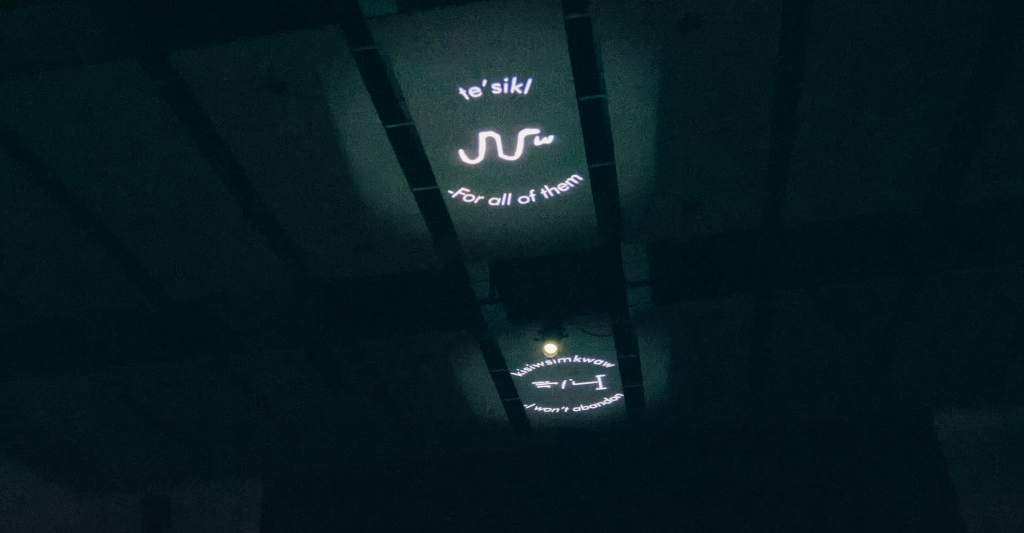

We enter a darkened hall. Tall, triangular boxes are placed in the centre of the room, with seating arranged in a circle around the space. When a sensor inside the box is activated, a light projects a message upward onto the ceiling in Komqwejwi’kasikl, English, and in the Latinized L’nuk language. The messages are to the children who never came home from residential school, gathered from community members during previous iterations of this project. As people weave through the room the space above us lights up with messages.

I respect

You are there

For all of them

Let us take care

All of them

Listen to us

I won’t abandon

They love you

We honour you

We did not take care

It is possible

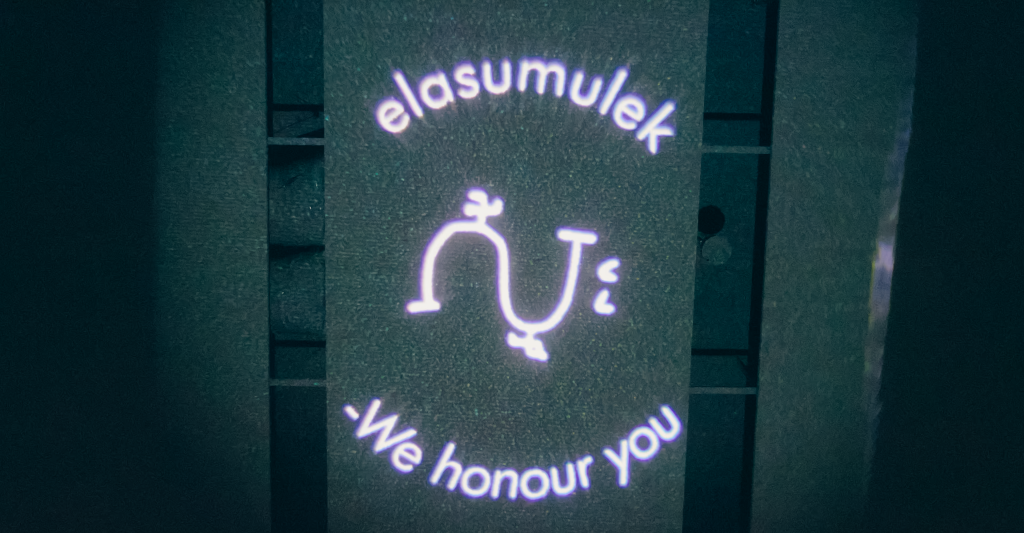

Inscribed on each light box is a eight point star surrounded by a circle and eight pipe shaped marks that represents chiefs of the seven districts of the Mi’kmaq Nation. This symbol is taken from a precolonial petroglyph located in Bedford Basin Nova Scotia that demonstrates the existence of L’nuk language before European settlement. Beneath the petroglyph is the image of a sprout emerging from a pile of soil, a reminder that the language and experience offered in this space comes from the land.

Music, song, and storytelling are integrated into our encounter. T’uy’t’tanat–Cease Wyss from the Skwxwu7mesh and Sto:lo Nations opens with a song that was sung when First Nations leaders traveled to England to demand the protection of their land, a reminder of host nations rights to and stewardship of the land that we’re on. Led by Renae Morriseau, musical powerhouse M’Girl share a series of songs that voice the emotional impact of residential schools, singing in beautiful harmony to the beat of a drum while dressed in swirling ribbon skirts. Their performance includes a lullaby by late Nlaka’pamux elder Shirley James and a song of healing to honour all life from Morriseau’s brother. Heather Hays, who plays with the Vancouver Opera, accompanies our meditative experience with the deep and solemn sounds of her cello. Loretta Williams, from Tswwassen Nation, also jumps up to spontaneously offer memories of Sylliboy and respect for the work that she’s doing. The gathering feels like a coming together of community, a ceremonial space to honour the children lost in the residential school system and heal the survivors who have experienced its impacts.

Little children our beings they found you – mijua’ji’jk ntininaq weji’skesnik emerged immediately after the remains of the initial 215 children were found at the Kamloops Indian Residential School site. As a federal day school survivor, with many in her immediate family also forced to attend residential school, Sylliboy understands the devastating generational impacts of this system of assimilation. Yet for all violence embedded in this history and the rage that it can rightfully provoke, Michelle responds with quiet and careful work that emphasizes not anger, but healing. As more children are found across the country, a dangerous hoax that is gaining traction in public opinion denies the existence of residential schools. Concurrently, despite the evidence there are people in Canada who participate in the erasure by denying the stories, knowledge, and sovereignty of Indigenous peoples. Sylliboy states that her work simply asks for acknowledgement. However, settlers must ask how our actions can go beyond acknowledgement to challenge the systemic issues that perpetuate the settler colonial project. Collectively, we must take up our responsibilities to the children who were taken away and protect those to come.