October. 13th, 2023

VIVO Media Arts Centre

8:30pm

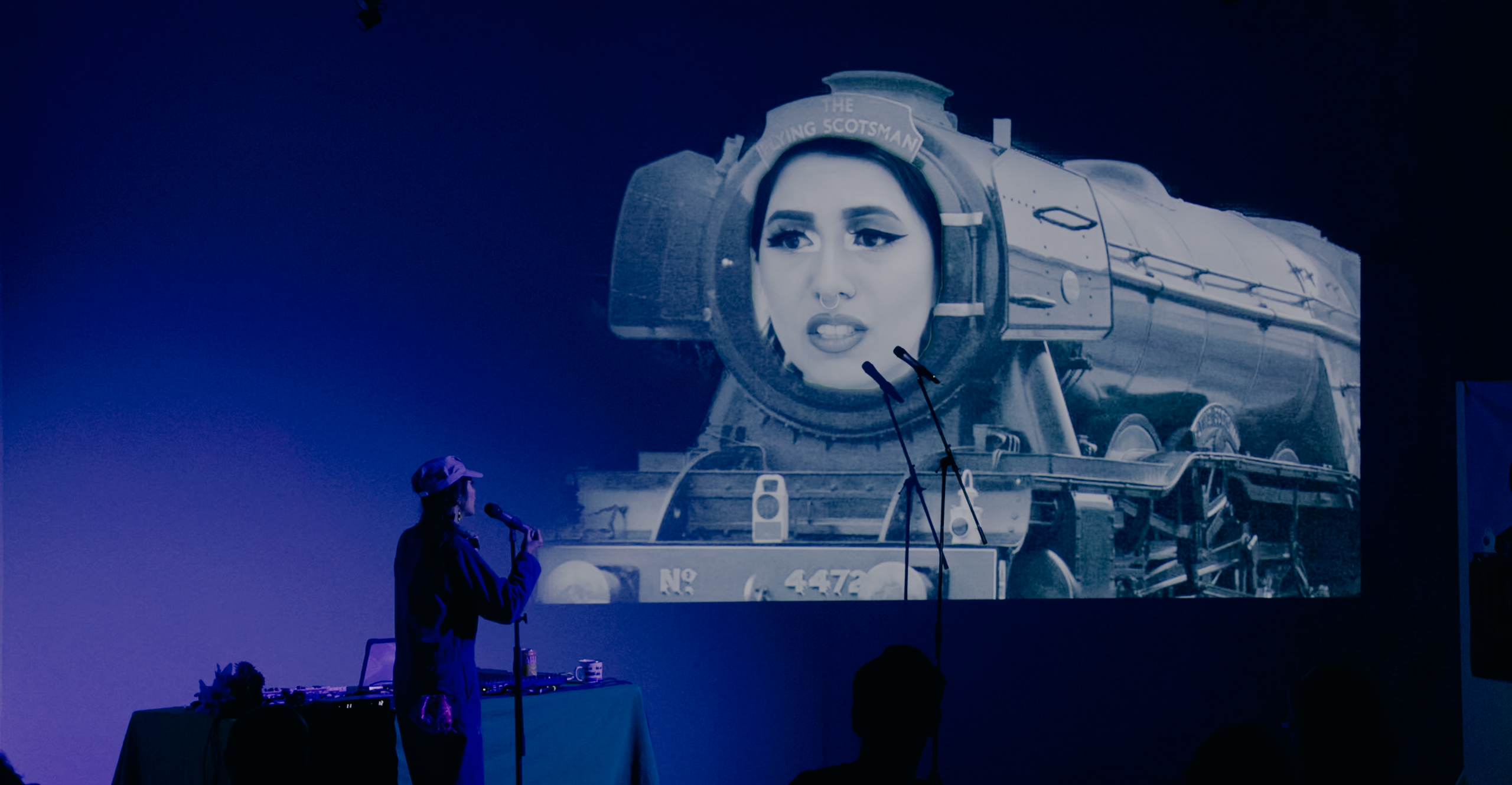

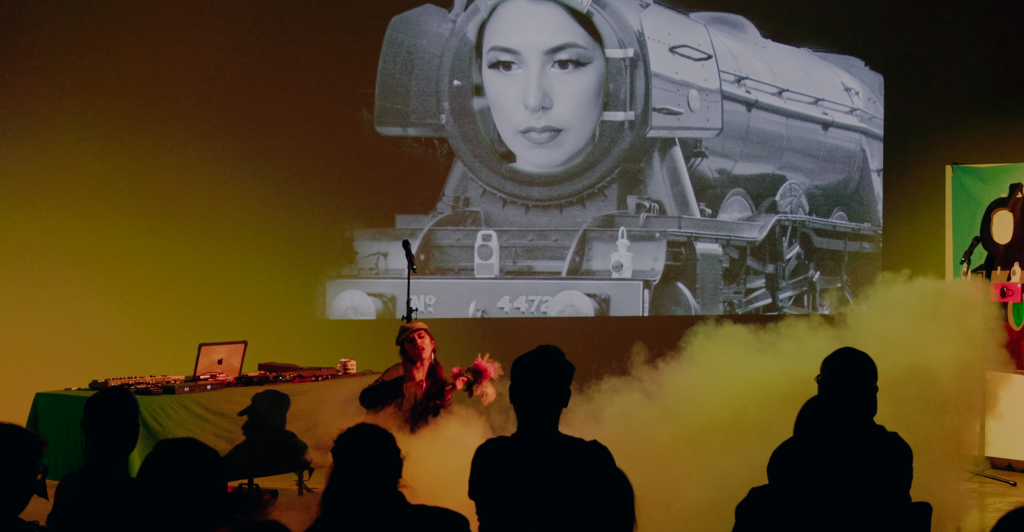

Megan Arnold’s A Tender Engine is a queer-reimagining of the romance between a steam locomotive, the Flying Scotsman, and “her” first caretaker, Alan Pegler. Developed during Arnold’s MFA program at the University of Guelph, this 50-minute hybrid performance art piece blends experimental theatre, musicals, and alternative comedy. In this one-person work, Arnold narrates, plays all the characters and operates the tech, weaving a semi-fictional multi-media tale of romance, bankruptcy and British locomotive history.

Description

In front of a seated audience, Arnold used a table of A/V equipment to set the scene, dimming the lights before slipping behind a large hand painted cut-out of the Flying Scotsman. As narration about the train and Pegler’s first meeting played in the background, Arnold brought the Scotsman to life through a merging of historical chronicling and theatrical humor.

“The Flying Scotsman story is complex, layered,” Arnold explained. “It’s a story of nostalgia, passion, cultural preservation, big sexy locomotives, the pathetic dregs of a crumbled empire, optimism and looove.” This narrative meeting point of colonial transportation and man/machine relationships unfolded through strategic dialogue, theatrical props, and multiple unconstrained musical performances. Fiction and fact collided as Arnold combined spoken word, documentary clips, astrological readings, and multiple lip-syncs of both pop culture songs and originals. Highlights included Bruno Mars’ “That’s What I Like” as Pegler’s serenade to the Scotsman, Ozzy Osbourne’s “Crazy Train” as the Scotsman’s empowerment anthem, and a final romantic duet performed by Pegler and the Scotsman, with Arnold singing both parts, swapping back and forth between painted cut-outs.

In this performance, the Flying Scotsman became a multi-talented gender-fluid muse, a locomotive whose power and allure bankrupt multiple millionaires over her life time. Pegler became a heartbroken, train-obsessed man clinging to the golden age of steam travel. The performance concluded with a fictional twist: as miniature trains rose on bundles of helium filled balloons—symbolizing the freeing of the steam engines—humanity was left to confront the economic collapse caused by their obsession with this particular form of technological advancement. This quirky, musical retelling of the Scotsman’s legacy left the audience simultaneously laughing and pondering the pitfalls of this longstanding colonial romanticization of rail transportation.

Interview with Megan Arnold

by Weiyi Chang

November 2023

One hundred years ago, in the town of Doncaster, England, Flying Scotsman was born. A Pacific-style 6-4-2 steam engine, Flying Scotsman became an icon of British engineering and a potent symbol of the empire’s prestige and power in the modern era. She was the first steam engine to complete the 631 km London-to-Edinburgh route non-stop; the first to reach 100 miles per hour; and the first to star in her own eponymous feature film. Celebrated as a marvel of technology, Flying Scotsman represented the best of British engineering at the 1924-25 British Empire Exhibition.

It was there on the storied grounds of Wembley Park that Alan Pegler—Flying Scotsman’s primary proprietor—first encountered the iconic engine. The heir to an industrial fortune, Pegler finally reunited with his beloved in 1963, when he rescued the newly retired locomotive from the scrap heap. Driven by a mixture of love and madness, infatuation and recklessness, the unlikely couple began running excursions across the United Kingdom, United States and Canada. Their cross-continental journey eventually bankrupted the industrialist, forcing him to abandon Flying Scotsman stateside. Bereft of her patron, Flying Scotsman was eventually repatriated to the United Kingdom in 1973 at the expense of her newest suitor. She would then pass through the hearts and wallets of one more millionaire, leaving behind a legacy of financial ruin and betrayal, before finally coming to rest at the National Railway Museum in York in 2004.

Megan Arnold reimagines Flying Scotsman and Pegler’s tumultuous affair as a tragicomic tale of star-crossed lovers in her one-woman performance, A Tender Engine. Debuting on the 60th anniversary year of Pegler and Flying Scotsman’s union at Vancouver’s LIVE Bienniale, Arnold’s performance marks the artist’s first post-graduate foray into the world of performance art. Her playful loco-erotic interpretation blends narrative tropes and techniques from the worlds of drag, stand-up comedy, music, video, astrology, and performance art into a highly original and comedic reflection on the dizzying, unwieldy power of love.

For Arnold, the romance between Flying Scotsman and Pegler exemplifies the mystifying power of love and its role in driving human (and locomotive) history—a central theme throughout her practice. What kind of madness drove three separate millionaires to bankrupt themselves for the love of this iconic steam engine? And how did the engine manage to seduce, not just Pegler and his ilk, but also the British national imagination? Arnold holds up to scrutiny the ineffable, inexplicable love between man and machine, how infatuation can drive otherwise reasonable people to extremes, and the grip Flying Scotsman held over the British imagination during the fall of the British Empire.

The following interview is a transcribed and edited version of a conversation that took place over the phone and by email in November 2023.

Weiyi Chang: Can you tell me a bit about yourself, your background and your artistic practice?

Megan Arnold: My practice is a mix of performance, video, and music. I still maintain a bit of a drawing practice as well. Drawing is what I have been doing the longest and music is a second. I’ve been making original music and performing it live for ten or twelve years or so. I started getting into performance at the end of my undergraduate degree, but I didn’t know how to find an audience when I finished school so I put it away for a bit. I was mostly drawing comics and making music when I decided to move to England in 2019 to do more performance work. When the pandemic happened, I still pursued performance further virtually.

WC: What was it that made you decide to expand your practice into performance?

MA: I found cartooning really lonely. I didn’t know if anybody was reading my comics and I couldn’t tell if anybody cared. I spent hours and hours alone in my basement apartment just drawing by myself. Something that I really loved about performing music was that kind of immediacy of being in a space with people. It made me feel like what I was doing was for more than just me. It felt a little more connective.

I’m not a very prolific artist by any means. With my music, I was getting bored of playing the same songs over and over but I didn’t have the urge to write any new ones. In school, I was also looking at a lot of comedy. We had this visiting artist series and Bridget Moser came to one of them and Shannon Gerard. They came in my third or fourth year and I was like, “whoa, you can do this in art?” I didn’t know this was allowed. Seeing them and looking at alternative comedians—especially Reggie Watts—I began thinking about how I could take the stories that I was putting into my cartooning and make them into a thing that happens through my own body, live in space in front of people.

WC: In addition to Reggie Watts, Bridget Moser and Shannon Gerard, are there other performance artists, contemporary or historical, that you’re thinking through or inspired by or other performance art traditions that you’re drawing from?

MA: I’m really influenced by the Doored series in Toronto, Life of a Craphead’s experimental comedy performance event that happened for ten years or something. I’m also hugely influenced by a lot of British comedians and live artists, because that’s really where I developed my knowledge base. There’s North Wave, which is an alternative comedy group in Northern England; the performance duo Cade & MacAskill, who make theatre-adjacent performance and live art; David Hoyle, a queer cabaret legend; and then Stacy Makishi, who is a Hawaiian-born, London-based artist who also makes theatre-adjacent performance art. She was also my mentor while I was in Manchester.

WC: Can you tell me more about your mentorship with Stacy?

MA: I fell in love with Stacy’s warmth and wackiness when she was the instructor for the New Earth Theatre Academy, so I applied for a Developing Your Creative Practice Grant through Arts Council England. I didn’t have any projects on the go, so Stacy mentored me in a very general way, offering exercises in devising, improv, and writing. She is an amazing storyteller. I got a lot out of just being in her presence, though we still have never met in person!

I was sad to have to end our “official” mentorship as the funds ran out and I moved back to Canada, but I was lucky to have a great thesis advisory committee for my MFA at Guelph. FASTWÜRMS, especially, were a huge influence on how my practice has evolved in the last couple of years. (The train whistle in A Tender Engine came from Dai’s family!) Both Stacy and FASTWÜRMS really foreground love, magic, and queerness in their practices, which are themes I’ve been attached to for several years.

WC: Can you tell me about your experience in Manchester’s art scene? How did you experience that shift, and how did it open up new avenues of artistic knowledge and exploration?

MA: It felt really affirming. I found this community pretty quickly. I had seven months between moving there and the first lockdowns and within that seven months, I was going to this alt-comedy open mic regularly called Entertainment Club, I was being asked to perform, and I found this community that was open to letting people try stuff out that was maybe weird and didn’t fit within particular genres. I chose Manchester ironically because of its music and drag scenes, neither of which I experienced, but I ended up falling in with the alt-comedy, weird, clown performance scene which I really loved.

But it was also a very difficult shift. I took having a tight community for granted and I thought it would be easy to make friends, but it definitely was not. Then when the pandemic and lockdown started, it was very hard to keep connections with those communities because everyone was hit so hard and unable to do these things. All this virtual stuff was happening and I thought, “why am I even here? I may as well be at home.” But I stayed for the full length of my visa and I did end up getting a lot out of it and I learned a lot about theatre too, which I had no previous experience or even interest in.

WC: Did you first learn of the story of Flying Scotsman and Alan Pegler in Manchester?

MA: Yes, during one of the lockdowns, I saw a documentary about Flying Scotsman and got hooked on the story. It was super weird and exciting. The thing that I liked most about the Flying Scotsman story was that she bankrupted three millionaires and yet, there was nothing about how Flying Scotsman is cursed! “No, she is the best, she is worth going bankrupt over…” Everybody is obsessed with her. And I wondered, what is it about this train that makes it a noble venture to bankrupt yourself to keep her running?

It stuck in my mind for a while, but I didn’t come up with a play immediately. When I was in grad school, I was listening to a song by one of my friends that is in A Tender Engine that he had written years ago called Boxcars, about the end of a toxic relationship. I was in the best relationship I had ever been in and falling very deeply in love at the time, and I was thinking about relationships and love and then I thought about Flying Scotsman and all of her admirers as I was listening to this train-themed song. I started imagining more of the romance of the story, and the queerness of the story. My partner is also very into old machines and vintage cars, so I was trying to consider the draw to machines, the life of moving parts and metal, and trying to see the romance in that too.

WC: Can you tell me more about the development of the performance?

MA: At the time that I was listening to this song and thinking about these things, I was also learning how to use DMX lighting. I would go to my studio on campus and I used the song as a base point to make a very short performance that used DMX lighting just to learn, and then I made a train cutout just out of foamcore; that ended up being a thin plywood prop in the duet, but at first it was just a really shitty cut-out thing. My partner grew up on a farm and he was taking me to the Fall Fair where he grew up and so the aesthetic is influenced by that. To do the duet, I made a video of Alan—Alan was in the video beforehand and I was Flying Scotsman—where he has my eyes and mouth and we’re singing to each other as this soft, semi-romantic lighting is happening. So I guess, to say all that, it was an experiment in lighting.

WC: What do you make of Alan Pegler’s obsession with Flying Scotsman now that you’ve created this performance? Did the process of developing and performing this character change the way you understood him as a person, his motivations, his love?

MA: I interpreted his obsession as romantic love because that was the only way I could connect with the story at first. When I was initially considering it as a potential performance, I was also appreciating my partner’s commitment to fixing old junk, keeping things running when most people would give up and send it to the scrapyard. That’s what softened me to Alan at first – thinking of him, not so much as a posh guy who wanted to possess this symbol of power, but as someone committed to extending the life of an object that would otherwise be scrapped.

A lot of the historical focus is on Alan and Flying Scotsman together, less so William McAlpine and Tony Marchington, and I think that’s because Alan had Main Character Energy. He’s described as eccentric, passionate, a “sentimentalist.” He built a career as a performer after he and Scotsman split! Like a horoscope, I selectively picked out the things that I liked in his biography and ignored the rest, and then projected my own simultaneous experience of a warm, obsessive love onto his character.

Obsession and fan culture are very much linked with Flying Scotsman – to promote her centennial exhibition, a couple told a story in a video of how they got engaged aboard her. Some of Alan’s ashes were actually scattered into Scotsman’s firebox after he died—I didn’t make that up. There’s a line in “A History of My Brief Body” by Billy-Ray Belcourt that goes, “My world had become so tiny you filled it entirely. Is that so wrong?” Obsession and fanatical excess can be red flags, but not always. Sometimes it’s just love!

WC: Throughout A Tender Engine, Flying Scotsman is gendered as a woman, which reflects a common trope amongst machinery. For example, ships are often gendered feminine.

MA: Part of my thesis was that machines tended to be gendered feminine for two reasons. One is the objectification of women and the other is to protect straight men from potential queerness, and desiring a He/Him or an it. I was being very intentional about using She/Her for Flying Scotsman as a way of drawing attention to that. She isn’t just a symbol of power, she is an object of power, she has agency, she is the desired, and so I wanted to give power to She/Her.

WC: At multiple points during the performance, you describe Flying Scotsman as a symbol of “modernity, speed, class, power, influence.” For me, as I was watching the performance, I read it as an analogy of Britain’s waning colonial power. It’s post-World War II, many of these former colonised territories have become independent or are in the process of declaring independence, steam power and Britain’s economic influence is on the decline while there is the ascendance of America…

MA: Something that I was really struck by after moving to England was how much the average person there does not have to think about Britain’s colonial impact. I was not used to having to explain what a residential school was, for example, and so I was noticing a lot of this naivete or ignorance to things that, to me, were very obvious symbols of this imperial past, like the monarchy and steam locomotives and things that I would consider outdated. I was also spending so much time with East and Southeast Asians through the performance and play writing workshops I was taking, and learning a lot also about Hong Kong and the very recent grip of the empire that Britain was clinging to.

WC: On the topic of comedy, I read elsewhere that you think of humour “as a coping mechanism to deal with anxiety in the face of an impending apocalypse.” Could you elaborate on your relationship to comedy, how you integrate comedy into your artistic practice, and how a comedic approach shapes your understanding and interpretation of these global narratives?

MA: Comedy has been in my practice forever, ever since I started drawing when I was little. That’s what pushed me towards cartooning as a young artist. I knew you were allowed to be funny as a cartoonist, but I didn’t know that funny performance art was a thing until I saw Bridget Moser perform. Part of it is cultural—my mom is Filipina and my dad is white and they didn’t always understand each other’s jokes, so I developed a sense of humour that was hybrid. I watched a lot of British comedy on TV, even when I was really little. I was also a shy person, and humour and comedy has been a way to make me feel good about myself and to get positive reinforcement from people. I think it felt really natural to transition into performance once I realised that it didn’t have to be self-flagellating and serious all the time. It was a way to process.

There is something really special about that feeling of communitas within a live event, of being the performer and conducting energy in a way that kind of pushes people towards each other. It’s like a two-way signal. Another thing that I love about comedy in performance is that you can tell immediately who gets it by who is laughing and the laughter can also be really telling, like who is laughing at which parts. I read somewhere that sharing a sense of humour is like sharing a language and so it’s kind of like finding these threads and then pulling on them and then there’s another person attached at the other end.

WC: Do you think developing the performance helped you better understand your partner or develop a deeper appreciation of his draw towards machinery? Do you feel like developing the work brought you closer together?

MA: I hadn’t considered that before. I think I started developing a deeper appreciation of auto mechanics when I helped him change a flattened leaf spring on his [Ford] F150. We joked the F150 was kind of like his Flying Scotsman, and he ended up selling it a couple of weeks ago before it could bankrupt him. I got attached to that truck too; we spent so much time with it, we thought of it as part of the family. When you love an object, think of it as something with a life, it’s hard to think of it as garbage. This love and respect for objects and the resources taken to make those objects is something my partner is teaching me. The draw of machinery is still a mystery to me, but the draw of – as Alan phrases it in a different context in the performance– “restoration, preservation, conservation” makes sense to me in an anti-consumer capitalist way.